I recently met Elizabeth Bishop. Not met, of course. But still, I feel her handshake, and I can’t seem to let her go. It is a handshake I want to remember.

I’m surprised I’ve made it through this much of my life without giving much thought to Bishop. I’ve taught her poems, “Sestina” and “One Art”, but only, really, to teach about poetic form. Not ever to have my students think about Bishop herself.

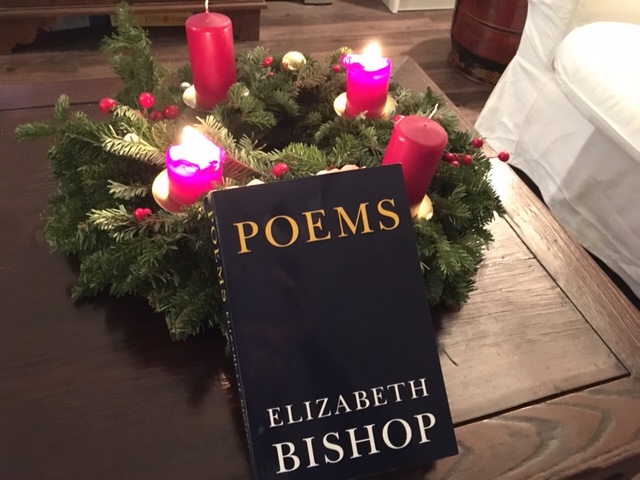

It was her poem “The Weed” that pulled me in last spring, and I’ve been devouring her collected poetry in Poems ever since. In “The Weed,” the speaker dreams that she watches a slight young weed / [push] up through [her] heart. It fascinated me, this idea of having your heart torn in two by a weed—a weed, whose growth both renews the life of a cold heart and whose pestering insistency also tears it in two. At the end of the poem, when the weed stood in the severed heart and the speaker wonders what its purpose is, the weed itself has the chance to speak: ’I grow,’ it said, ‘but to divide your heart again.’

This line embodies many of Bishop’s poems: the presence of sadness, even in joy or renewal.

The poems kept finding me, greeting me, welcoming me: “Squatter’s Children,” about a specklike girl and boy playing on the unbreathing sides of hills near aspecklike house, a poem inspired by Bishop’s time in Brazil ; “A Miracle for Breakfast,” in which the speaker believes there was not a miracle at all, though I think the greatest miracle in the poem goes unrecognized; “The Fish,” on whose lip —if you could call it a lip—…hung five old pieces of fish-line…with all their five big hooks / grown firmly in his mouth…like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, / a five-haired beard of wisdom / trailing from his aching jaw; and “Exchanging Hats”, in which Bishop seems to question society’s thoughts on gender-identification.

What marvels me about Bishop is the playfulness of her language, punctuation, and experimentation with form and rhyme, all juxtaposed to the often somber tone of her poetry. Her use of metaphor and the simplicity of her subjects make Bishop’s work approachable; even her handwritten drafts at the end of the book give more insight into her writing process—who she is as a poet and how her ideas changed over time. She becomes real.

I started reading Poems in the spring and am still working my way through. Now that she has come into my life, I am savoring her presence. I want this handshake to last.