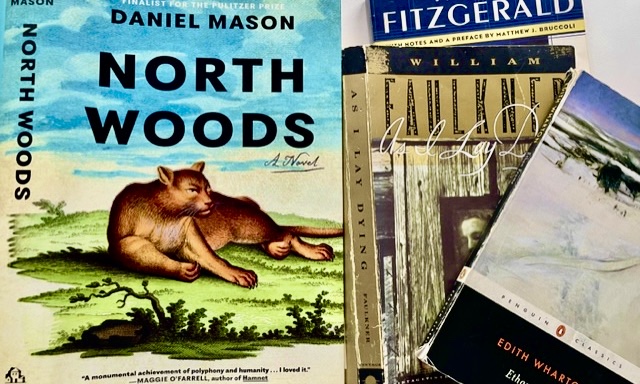

America – playground of the rugged individual, land of opportunity, home of the brave – has long been imagined as an Eden in a fallen world. Into its literary canon please welcome Daniel Mason’s brilliant North Woods, a book that is in intimate dialogue with Wharton’s Ethan Frome, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and “A Rose for Emily,” Miller’s The Crucible, and more recent greats such as Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo and Powers’ The Overstory.

Set in the Massachusetts wilderness, North Woods begins with a description of ecstatic lovers on the run from a Puritan stronghold: “Fast they ran! Steam rose from the fens and meadows. Bramble tore at their clothing, shredding it to rags that hung about their shoulders…They fled as if it were a child’s game, as if they had made off with plunder. My plunder, he whispered, as he touched her lips.”

Blindly trusting a passionate visionary who would save her from marriage to a violent minister twice her age, the unnamed woman is the first of many Eve-like characters to act hastily and on instinct, risking everything for the possibility of love and freedom. Likewise, this unnamed man is the first of many Adam-like characters to rebel, create, prosper, and succumb to elements and forces well beyond his power. Together they lay the literal first stone for the foundation of the house that anchors all of the narratives that ensue: “Here, he said… At the brook, he found a wide, flat stone, pried it from the earth, and carried it back into the clearing, where he laid it gently in the soil. Here.”

Over centuries of American history, this humble lodging becomes the site of a bountiful orchard, of amorous dalliances, of jealous betrayals, of animal invasions, of supernatural visitations, and of more than a few murders.

Injured English soldier Charles Osgood brings his twin daughters to this place when he discovers nearby a variety of apple so delicious that he dedicates his life to its propagation. Romantic painter William Henry Teale later moves to the house in order to escape the confines of both his marriage and polite society. Years later still, Anastasia Rossi, née Edith Simmons, visits the renovated house to conduct a séance with the wealthy but unhappy Mrs. Farnsworth, who hears voices that disturb her. It’s hard to choose a favorite character from this remarkable roster – none are particularly loveable – but it is easy to empathize with them all, even those who resort to violence.

Mason, a psychiatrist by training, seems both fascinated and amused by the unpredictable machinations of the human mind, a benevolent miner of a seemingly infinite quarry of human material. His characters have names and true dimension when they are living, but in the end, they are probably best remembered for the archetypes they come to represent: opportunists and madmen; devotees and charlatans; and loving, lonely, misguided “everymen” of the ongoing American morality play.

That their voices never actually disappear from the woods they called home is both a compelling fantasy and an homage to America’s deep affection for gothic tales and ghost stories, and to America itself – that fresh, green breast of the new world, its woods so very lovely, dark, and deep.