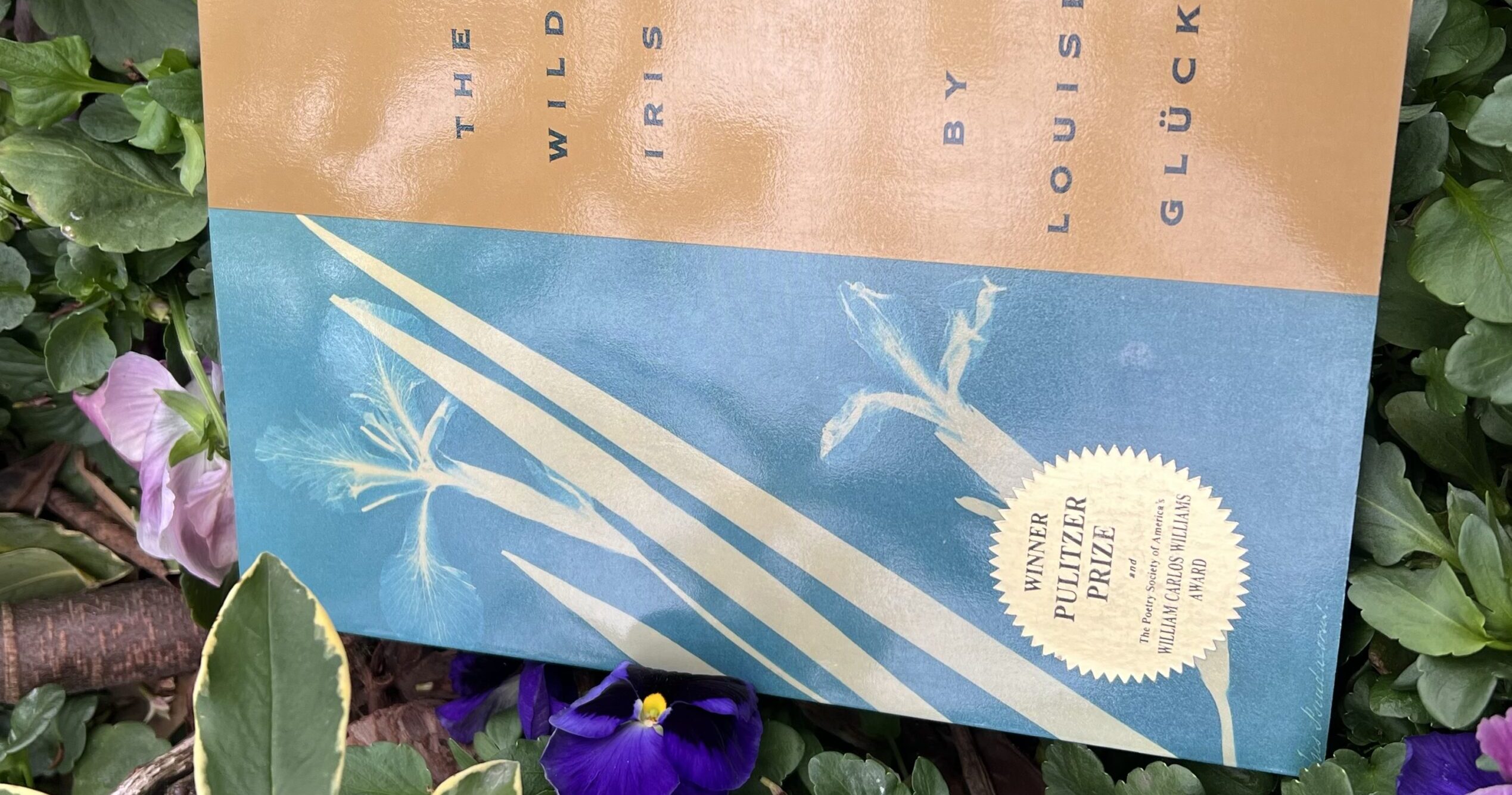

After the American poet Louise Glück died in November, I revisited her Pulitzer-Prize-winning collection, The Wild Iris. It’s a deliberate, haunting work meant to be read straight through: the poems reference one another and the three speakers are presented in dialogue throughout the arc of the book, which is, in Glück’s words, “the arc of summer” in a Vermont garden. The language is direct, precise, even spare, but questions of mortality and faith raise the level of complexity. Unlike many confessional poets, Glück uses the first-person cryptically, detaching the personal even as she allows glimpses into her own struggles.

Clues for how to read the poems are found in the titles: flower names signal that the “I” of the poem belongs to the flower itself, reaching for the sun, dying back into the earth, addressing the gardener. Poems entitled “Matins” and “Vespers,” religious terms for morning and evening prayers, are in the voice of the poet/gardener and address her frustration with God and allude to both her depression and her search for meaning. The last voice, found in most of the poems titled with time or place (such as “Clear Morning,” “Spring Snow,” or “Early Darkness,”) exudes a mysterious power and a gentle disappointment in humanity: this speaker is God-like, with a larger overview that is neither human nor of the natural world. Glück uses Biblical imagery without commitment to a reassuring Judeo-Christian faith. The poet—rational, suffering—dreading the onset of autumn, seeks to make sense of her estrangement from and need for this deity: “is pain/your gift to make me/conscious in my need of you, as though/I must need you to worship you,/or have you abandoned me/in favor of the field…”

The God of this garden as Glück imagines is neither comforting nor cruel; rather, the voice is at times frustrated with humanity in general and the poet’s questioning in particular: “Whatever you hoped,/You will not find yourselves in the garden,/among the growing plants./Your lives are not circular like theirs;/your lives are the bird’s flight/which begins and ends in stillness—…” Embedded in this book is the image of Adam and Eve, those first, exiled gardeners, reflected in the figures of the poet and her husband and in Adam and Eve’s legacy of balancing the pain of mortality with the knowledge of good and evil. In this case, the poet’s search for knowledge—of her purpose—is bound up in the ability to write, in her creation of the very poems we are reading. There is the trade-off of a retreating God, who bestows upon her “pencil and paper,” urges her to “write [her] own story,” then leaves: “Creation has brought you/great excitement, as I knew it would,/as it does in the beginning./And I am free to do as I please now,/to attend to other things, in confidence/you have no need of me anymore.” Here we see echoes of the Biblical “in the beginning” and the poet’s act of writing that mirrors God’s own act of creation. In claiming her voice, the poet suffers but gains the means to express it.

As the poet/gardener and the God/Gardener find and lose each other, the flower poems knit their struggle together with distinct, gorgeous voices. Occasionally uncomprehending, usually brilliant, the flowers observe the poet as their god, and in often tart assessments of her limitations, they flaunt their own beauty, cyclical nature, or ease with death. Glück’s poems are mysterious and powerful, and the cumulative effect of The Wild Iris is one of searching, grappling, and acceptance. The last poem contains all the multitudes of the book: the Biblical lilies of the field reference the original gardeners; the poet and her husband; the specter of loss; and the movement from temporal to the last, glorious image of rebirth.

The White Lilies

As a man and a woman make

a garden between them like

a bed of stars, here

they linger in the summer evening

and the evening turns

cold with their terror: it

could all end, it is capable

of devastation. All, all

can be lost, through scented air

the narrow columns

uselessly rising, and beyond,

a churning sea of poppies—

Hush, beloved. It doesn’t matter to me

how many summers I live to return:

this one summer we have entered eternity.

I felt your two hands

bury me to release its splendor.