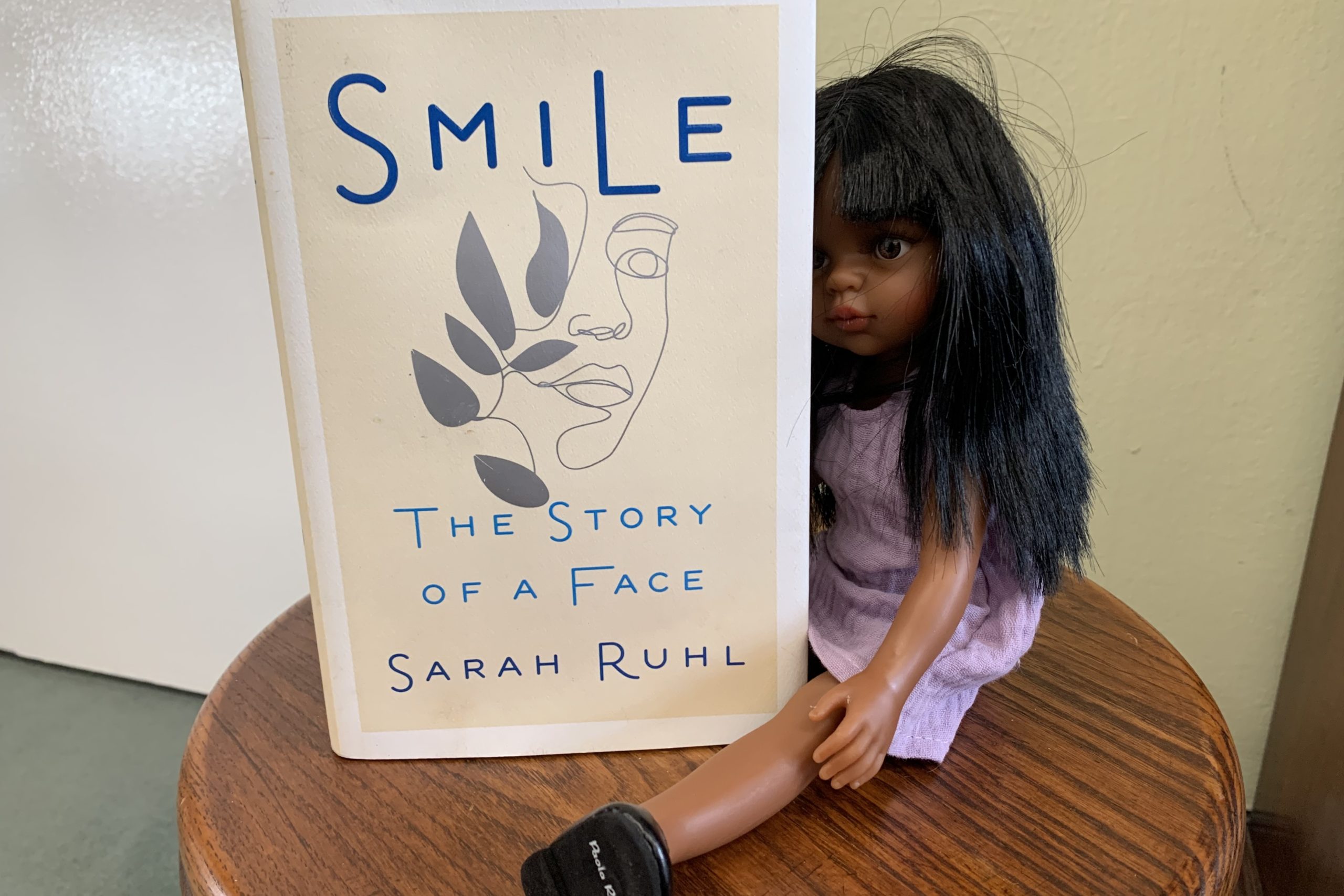

“Ten years ago, my smile walked off my face, and wandered out in the world. This is the story of my asking it to come back. This is a story of how I learned to make my way when my body stopped obeying my heart.”

In the first lines of this remarkable memoir, storyteller and playwright Sarah Ruhl invites us to accompany her on a saga worthy of a fairy tale. The intimate story of a mother and a wife and a writer is a tale of discovery–of obstacles and heroines, of a quest for a magic cure and of hopelessness and resilience. After the birth of her twins, Bell’s Palsy afflicted Ruhl’s face. It was impossible for her to smile, raise her eyebrows, or blink. Early on, Ruhl says, “In fairy tale logic, you must trade something for what you desire. By this logic, I traded my face for my children. And it was a fair trade.” Never does Ruhl regret or resent her healthy babies, but her acknowledgment of a trade she did not intend–babies for face–serves as the spine of her memoir.

I do not know Sarah Ruhl, but, oh, how I admire her spirit, her humor, her tenacity and her writing: plays, essays, and now, her memoir. I first read 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write: On Umbrellas and Sword Fights, Parades and Dogs, Fire Alarms, Children, and Theater as I began, about seven years ago, to think of myself as a writer. It is a marvelous collection of quick jottings, micro-essays, if you will, that are raw and honest and real. Because I am a life-long drama teacher, I love that Ruhl is a playwright. I also love that she claims, rather than hides, her identity as a working mother. Smile is a meditation on motherhood, symmetry, perceptions of beauty, agency, and the ways in which women, in particular, continue to be judged on their appearance, their friendly expressions. It is part memoir and part manifesto, told with such elegance and grace that it seemed as if Ruhl was sitting cross-legged next to me drinking tea in my living room. It’s also a little meta in that she lives with a changed face as she reflects on what changed faces mean–in her own life, certainly, but also in our culture.

“I never specifically prized my smile, but now I realized I used to have rather a nice one. Symmetrical and full. I began to feel what a loss it was not to be able to smile at strangers to indicate permission to speak, affinity or understanding.” Ruhl’s matter-of-factness made me ache for her. I had one face, she explains, and then I had another. What a transformation. She blames herself, as if she caused the frozen droopiness she loathes. It cannot be easy to lose command of one’s features–especially as a mom and as someone who spends her life in the theatre with actors, who reveal every nuanced expression on their faces. It would be unthinkable to me not to have been able to smile at my infants. Once you lose the ability to choose to arrange your features, you notice how others take that privilege for granted, day after day. Ruhl says, “I started admiring taciturn cultures where it is impolite to smile for pictures.” Her unflinching vulnerability in sharing her story moved me.

Ruhl has spent her life as an observer, but she is the star of her own story here: flawed, alternately depressed, hopeful, and hugely determined. Ultimately, hers is a tale of resilience and hope, but along the way, she offers us digressions that are purposeful, meditations on language and etymology that gracefully reinforce her narrative. That she is terrifically well read—forays into Bible verses and Greek mythology regularly punctuate the text—reminds me of how smart she is, but her style is unpretentious, conversational. In a sense, Ruhl’s individual story becomes a sort of Everywoman’s story. What do we ask of women and their faces?

The structure of the memoir is chronological, beginning with the birth of her twins, Hope and William, but because her Bell’s Palsy lasts a decade, we learn, too, about her life: marriage, motherhood, her writing, her plays, her struggles with depression, her intermittent determination to find a cure for her face, her Celiac disease and her Irish heritage. The chapters are quick and episodic, but the aggregate is a story that has stayed with me since I finished the book.

It was on NPR over a year ago that I heard Ruhl speaking about Bell’s Palsy. I immediately ordered the book and promptly forgot about it. Some months ago, I reviewed Suleika Jaoud’s memoir, Between Two Kingdoms, for bookclique. In that powerful story, I learned about Suleika’s friend, the poet, Max Ritvo, who was Sarah Ruhl’s student and friend at Yale Drama School. Ruhl wrote the story of their friendship in Letters from Max, a book that’s next on my list. In grappling with how to manage large swaths of time in a memoir I am writing, I was prompted by a wise mentor to read Smile. I’m glad I did.