It sounded straight out of an encyclopedia on dinosaurs.

“Cyto…megalovirus?” I wasn’t sure I was repeating it correctly.

“Yes,” replied the NICU doctor. “CMV.”

“And he got it from me?” But I’d followed all the pregnancy rules: no sushi, cold cuts, cat litter, runny yolks. I Purelled, got my flu shot. But it was one year before the advent of Covid, so I wasn’t yet trained in the science of surprise viruses. “How did I get it?”

“Could be a latent infection? It’s very common. Or a new infection from your toddler.”

“My toddler?” I thought suddenly of that horror trope: The calls are coming from inside the house.

“It’s in saliva and urine.”

All the kisses and shared drinks, all the sneezes right in my face over the past winter. Had I carefully washed my hands after every diaper change? And now my second born, not yet two days old, lay hooked up to a million machines in the NICU, his liver, spleen, kidneys, eyes, ears, skin, and brain attacked by a common virus I’d never heard of. And one, I would learn, remains the number one infectious cause of birth defects. Congenital CMV (cCMV) affects one in 200 newborns yearly in the US. After genetics, it’s the number one cause of hearing loss. Most children who contract it in utero are born asymptomatic. Many go on to live entirely unaffected lives. But a significant portion develop disabilities later. Hearing loss out of nowhere when they turn three. Vision issues. Developmental delays. Autism. Over the next few years, as I took Patrick to see nine different specialists on rotation—not including our regular pediatrician and the various phlebotomists I befriended at the hospital—I came to deeply respect and admire some of the kindest, most compassionate physicians and staff I’ve ever known.

But it was profoundly lonely. My husband and I knew no one else who was going through this. None of our friends, family, or colleagues had ever heard of the virus either.

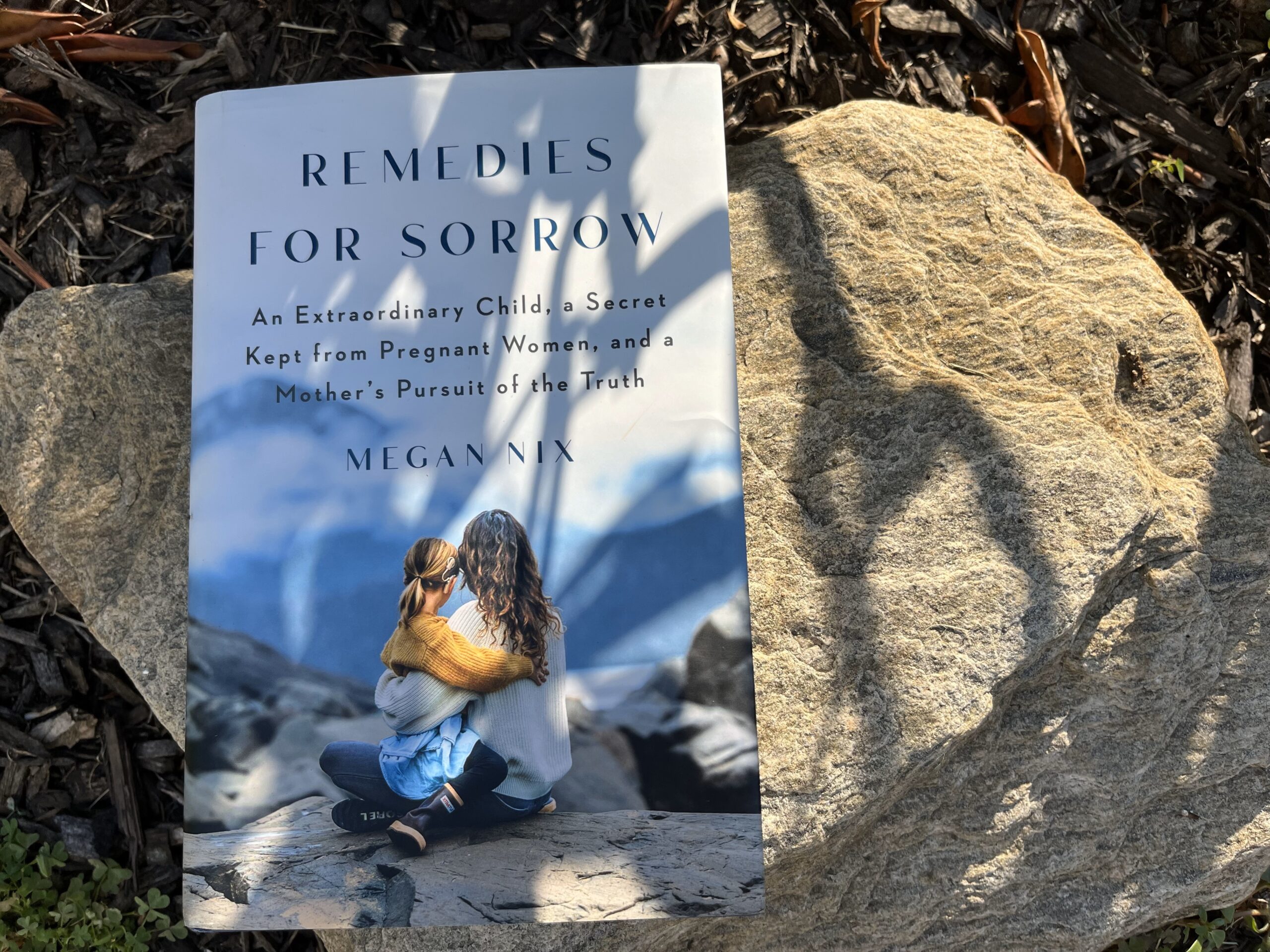

It was lonely, that is, until I read Megan Nix’s 2023 gorgeously moving book, Remedies for Sorrow. Nix, a nonfiction writer married to a salmon fisherman, and her family split their time between Colorado and Sitka, Alaska. When their second child, Anna, was born, small and profoundly deaf, Nix too joined the club of parents unexpectedly thrust into the tumultuous wake of cCMV. But unlike my husband and me, who hunkered down and tried to move on with our lives, Nix decided to do something about it. She dove deep into all the studies on cCMV, sought out other parents, questioned physicians about the lack of cCMV education for expectant mothers. She became an activist and writer.

Nix’s book is part medical exploration of this too-long-ignored virus, but it’s also a wonderfully absorbing memoir—about the revelations of motherhood, the world of deafness, and life in Alaska. Her descriptions of Sitka made me yearn to raise my children in a place of such wild majesty. To live on the far edges, a life less ordinary, where you need an hour-and-a-half boat ride and then a raft just to reach a two-mile hiking trail that will take you to a stunningly expansive beach. In the scene that describes this particular trek, Nix, watching her older daughter bound down a bear-print-lined trail, experiences a revelation: “Watching her appear smaller ahead, I realize that somewhere along the line, I’ve confused protecting her with controlling her. Glancing down at Anna in the pack under my chin, I know that if I’d understood this during pregnancy—that protection is love, but believing we can control any outcome of our children is not—CMV would have been just one more species to understand in the brimming wilderness of parenting.” Later, she reflects: “Maybe I’ve been so awash in the anxiety of our parenting culture, so governed by worthless competition and impossible perfectionism, that I’ve forgotten—or I never knew in the first place—that my capability and capacity have nothing to do with the way I look, the way my kids behave, the diseases they have, or the way a day begins to deteriorate.”

Some chapters left me in tears and some left me breathless. Nix meets a few mothers who have children more seriously affected by cCMV than Anna, children who know little of life beyond seizing and being held, and children who died early. In one chapter she explores a little-known publication titled The Pedagogy of Innocent Suffering. Just before his death in 1956, an Italian priest named Father Carlo Gnocchi wrote this spiritual reflection on why children must suffer. He had been a Military Chaplain in Milan during the Second World War, witnessing more than his share of inhumane atrocities, particularly those suffered by our the most vulnerable. What he arrives at is both firmly rooted in Christian theology and radical: “To a child who suffers from a disability, deficiency, mutilation, poverty, sickness, ignorance, abandonment, or from any other cause, our internal disposition or external attitude should be dominated by a profound feeling of respect and veneration. I would almost say that it should be of worship.” Nix summarizes his reflection well: “In these children, we can encounter something much more meaningful and vast than our singular, human experience. […] The disabled are not just worthy of being included in politically correct advertisements, but perhaps they’re of even more value to humanity than the children we consider typical or high-achieving.”

I think we will always worry—and wonder—about Patrick. He’s an immensely energetic, affectionate, and imaginative child. He’s got a wicked sense of humor and is on track to start kindergarten with his peers. But what residue has cCMV left in his body and brain? Can the virus claim his quirks and challenges or are they entirely his own? But these are impossible questions. And besides, while I wouldn’t wish cCMV on anyone, the experience of being his mother has indeed been something much more meaningful and vast.

I could write much more about this book and about my own experience with cCMV and the effect that Nix’s powerfully chronicled experience has had on me. But I will only add that I highly recommend it. To anyone who cares about our healthcare system, illness, disability, or about the sufferings and joys of motherhood. And to anyone who just enjoys a damn good memoir.