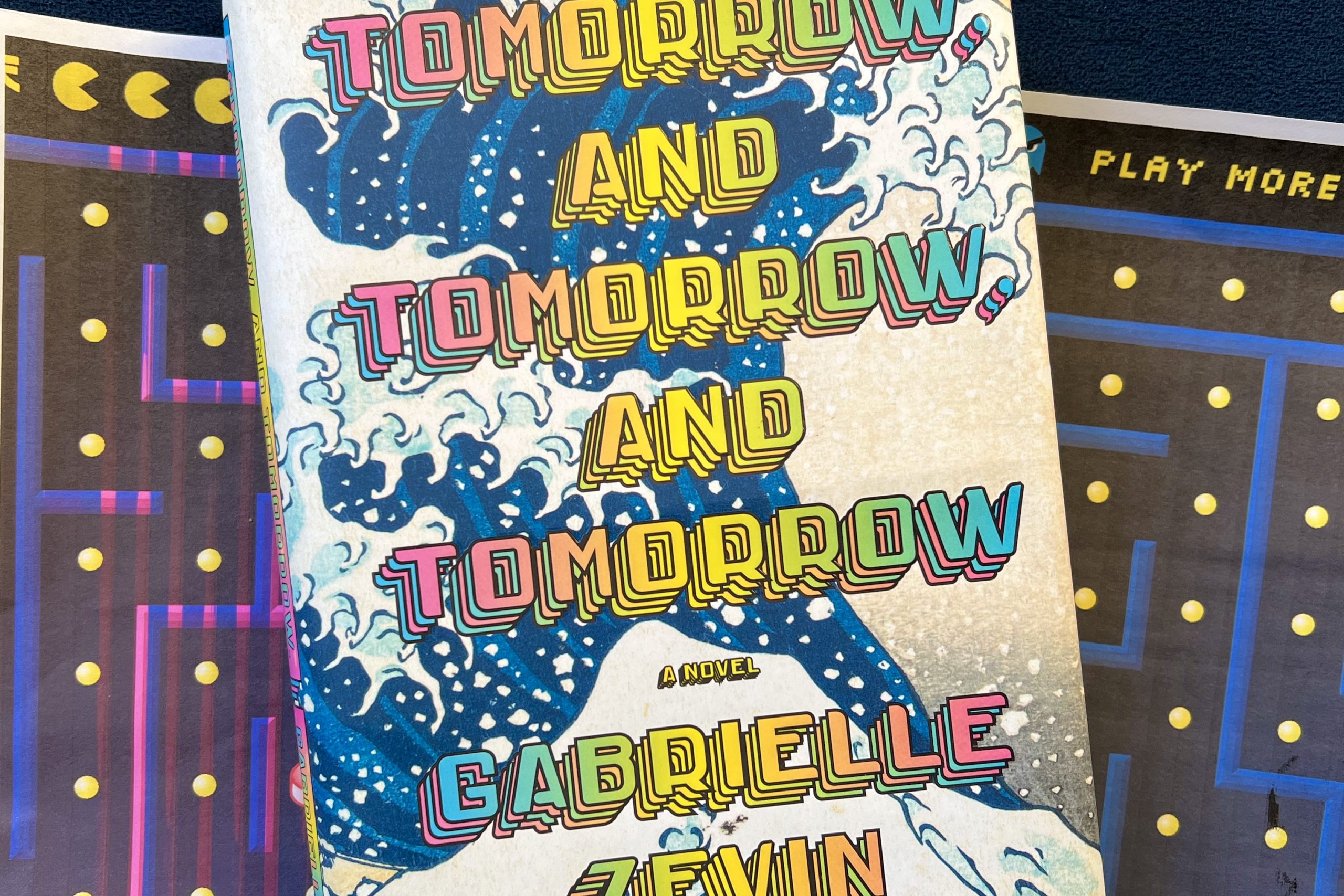

When I say that “playing” Pong in the early 1970s was my first and last experience with video games, I am not kidding. I was a horse girl. I read a lot of books. I discovered boys. None of those boys were Pokémon boys. My hand-eye coordination was unimpressive; my interest in warfare or go-kart racing was nonexistent. My children resisted the enticements of Sims or Solitaire on a PDA. Frankly, I thought PDA was what happened up against a school locker. How delightful, then, that my favorite book of 2022, Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow introduced me to, seduced me into, and convinced me to re-examine the (who knew?) fascinating world of gaming. Of course, the title’s allusion to (and the novel’s ultimate challenge of) Macbeth’s soliloquy is our first clue that Zevin is a literary writer who insists that the creativity of making video games is akin to the creativity of making art, and that the immersion of gamers in their worlds is no less enriching than the immersion of readers in theirs.

Zevin writes flawed, spiky, ultimately lovable characters, namely Sam and Sadie, who meet as children playing Super Mario Bros in a hospital game room. Her weaving of past and present; the leisurely unspooling lives of these characters incorporating humor and tragedy; and a sprinkling of avatars and infinite secret highways are the key reasons this novel resonates so deeply. We follow Sam, whose success is both spurred by and masks his emotional and physical pain; Sadie, whose struggles as a woman in a male-dominated industry shape but never define her; and their friend and producer, the generous Marx, whose love for these prickly geniuses is a bond and a betrayal. There are no one-note characters, not Sam’s enigmatic Korean mother, not Sadie’s married professor Dov, who is predatory and supportive. Connected in a way that is never explicitly romantic, Sam and Sadie form the book’s most vulnerable and powerful relationship: a creative partnership that flourishes and wanes, brings them fame and fortune, results in failure and triumph, and is based at its core in their inventive play, in their true collaboration.

During a rebuffed attempt to name their game company, Marx, once an actor, performs Macbeth’s soliloquy from atop a kitchen chair, trying to convince a bemused Sam and Sadie: “What is a game? It’s the possibility of infinite rebirth, infinite redemption. The idea that if you keep playing, you could win. No loss is permanent, because nothing is permanent, ever.” Though the novel provides heartbreaking proof that Marx’s optimistic view is wishful thinking, it also finds precious hope in the reboot, perpetuity in the game’s ghosts, and a life-affirmation that challenges Macbeth’s despair.

Not only does Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow entertain and instruct in new (to me at least) ways, it also contains excellent writing, including two of my favorite chapters, one an achingly poetic, second-person flight that brought me to tears; the other an imaginative immersive game that meshes the book’s themes, symbols, and characters and leads to healing. In the games that populate this book, inventions that are deeply personal; that invoke Emily Dickinson, the Holocaust, pioneers, or lost children; that are an expression of reconciliation and forgiveness, the characters attain a kind of immortality. As one of Sadie and Sam’s games asks each time the player dies: “Ready for a new tomorrow?”. I can’t imagine anyone who wouldn’t love this book. I finished it curious about taking up gaming though stymied by lack of equipment and follow-through and not enough helpful teenage boys in my life. Better just to wait for Zevin’s next novel.