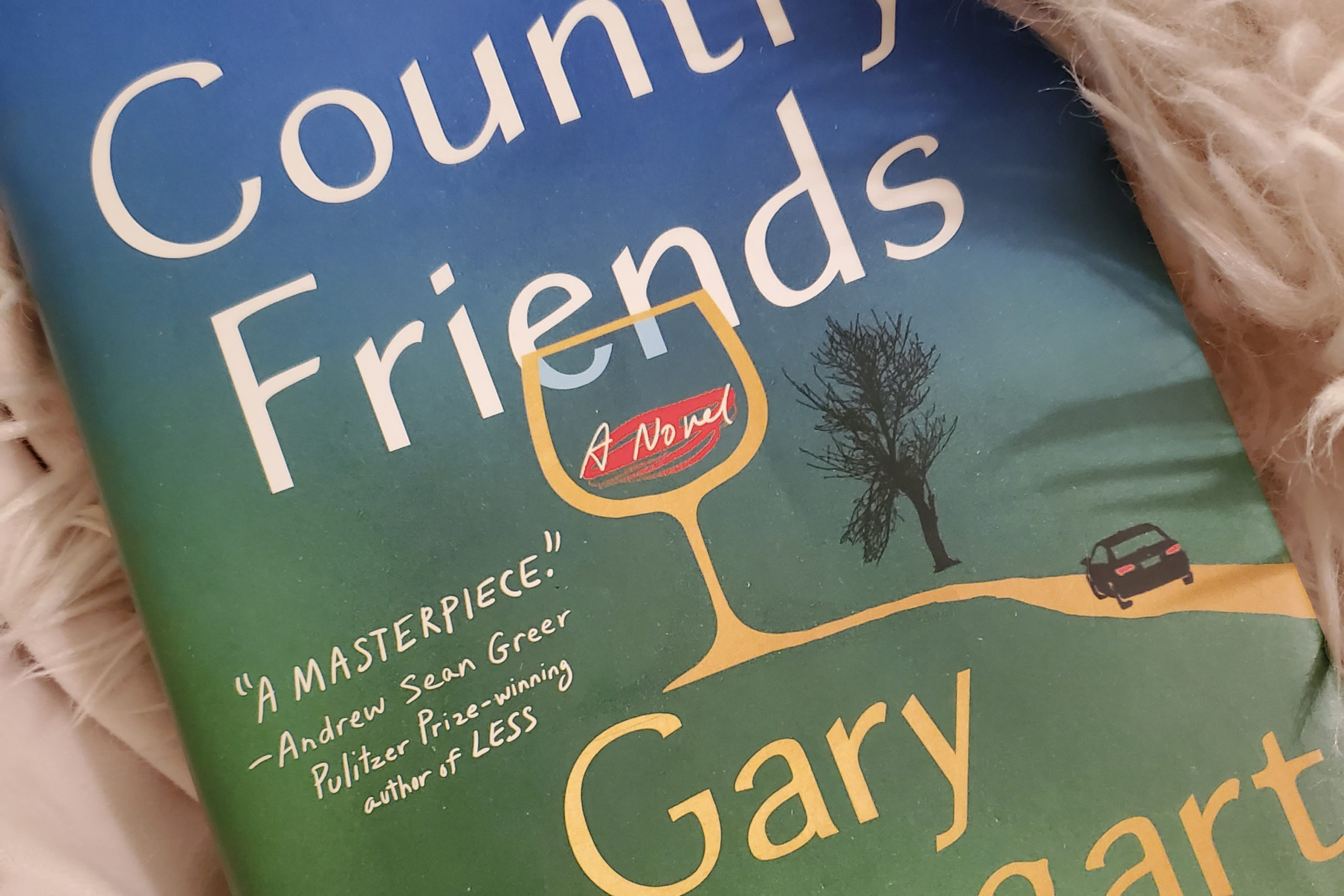

Gary Shteyngart’s Our Country Friends is both an extremely funny and an achingly melancholic portrait of the beginning of the Covid era. Shteyngart’s main character, Sasha Senderovsky, is a floundering writer in his 50s. His wife, Masha, is a psychiatric doctor. Their adopted daughter, Nat, is a precocious eight-year-old, obsessed with K-Pop. The family invites a group of literary and creative friends to join them at their Hudson Valley estate, which they consider to be a kind of Russian dacha. The intent is to ride out the pandemic together.

Through his sardonic narrator, Shteyngart offers us a mixed bag of delightfully-flawed characters. He gives us Karen, the wealthy inventor of a dating app which manipulates images to make people think that they are in love. (The app’s name, “Tröö Emotions,” is an umlaut enthusiast’s dream.) He presents Vinod, the talented, unpublished writer, whom he poignantly describes as a “former adjunct professor and short-order cook.” He gives us Ed, a wealthy and cultured Korean “gentleman,” who once reminded Sasha “…of a film he had seen about China’s last emperor, specifically the dissolute stage when the hero wore a tuxedo and was the puppet ruler of Manchuria.” He introduces us to Dee, an upwardly-mobile former student of Sasha’s who “…wrote with a disdain for week-bellied sentiment, mixed in with tough-love observations about the social class that had recently welcomed her into their messy brownstones.” And he offers us “the Actor,” a man who is so hot that no one (including the narrator) dares to speak his name.

These characters are more than caricatures, however. The narrator’s comic descriptions reliably pivot to provide insights into individual psyches and into American culture more broadly. For example, Sasha seems rather foolish at the beginning of the novel, as he collects a bourgeois assortment of groceries: fresh sardines, “lamb steaks that clung to the bone,” “glistening hamburger patties,” four cases of wine, assorted alcohol, and “an eighteen-year-old bottle of something beyond his means.” Later, the narrator shifts tone: “The very sight of the meat [….] inspired in [Sasha] a joy that in a younger man could be called love. Not because of the meat itself, but because of the conversations that would flow around as it was marinated, grilled, and served, despite the growing restrictions on such closeness.” Sasha’s excesses reveal his desire for intimacy and his fear for the future.

Our Country Friends is also a self-consciously literary novel, one filled with countless allusions to books and plays (most particularly to works of Russian literature). Shteyngart opens the book by presenting a list of its Dramatis Personae. These characters later stage a performance of Uncle Vanya (and film a documentary about the production). It would seem that Chekhov’s spirit haunts the dacha and the novel itself. So be warned: if you hear a dry cough in the novel’s opening scene, expect there will be a loss by the book’s end.

Reading Our Country Friends at the start of 2022 feels nostalgic—nostalgic for a time when the novel coronavirus still felt “novel”—that is to say, new, (presumably) temporary, and perhaps even able to be represented in literary form. Seventeen months after the timing of the book’s closing scene, many of us still experience brain fog and/or remain in some form of physical or psychic retreat. This leads me to a confession: Given that the arc of Shteyngart’s narrative is so closely tied to the arc of the pandemic, I became increasingly agitated as I neared the end of this book. I could not imagine how Shteyngart would provide closure.

In a way, he doesn’t. The novel’s final scene takes place in September of 2020 as a group of characters meet for dinner in New York City. As one figure (I won’t say who, so as not to spoil the novel’s suspense) waits for the check, they observe that a group of people dancing in the bike lane are: “…modeling happiness and impromptu pleasure with their own awkward gestures and composed smiles, facsimiles of what they had once been before all the knowing happened.” “Modeling” is a useful concept here. After all the loss and “all the knowing,” the people that this character observes actively use clichés, gestures, and facsimiles to get themselves going. Perhaps this is what Shteyngart wants for his readers. Great literature, such as Our Country Friends, helps us to recognize our absurdity, our magnificence, and our humanity. However, even the best books can only present a facsimile of life. It is up to each of us to choreograph our own dance moves and to determine what direction our stories will take next.