There are many representations of mothers in literature, from suicidal Edna in The Awakening to Hamlet’s sexual Gertrude. Mothers are self-sacrificing, comically demanding, heartbreakingly cruel, cozy and comforting; they are powerful protectors and selfish abandoners. I once taught a Women in Literature class at an all-boys school, planning a thematic exploration of the madonna/whore complex, but it turns out (unsurprisingly) that all the boys wanted to discuss was is she a good mother? When I had my own children, at what doctors charmingly called my “late maternal age” and after many miscarriages, I was privileged enough to tutor part-time from home with the help of a beloved babysitter. I was so lucky! Why then did anger swell in my heart when my husband put on a clean suit and escaped to a “real job”? Why resent the playground hours, those long stretches of boredom punctuated by flashes of terror as my darling toddled to the spinning metal contraption or frolicked in the forbidden NYC sandbox, a receptacle for rats and needles? Why did I judge the “working” moms leaving their babies to nannies; why did I judge the “stay-at-home” moms opining about organic baby food? And why did I judge myself most harshly of all? I was so lucky! I fiercely loved my hard-won, desperately-wanted, delightful daughters. But almost twenty years later I can still remember the blur of room-spinning exhaustion at 3 am, my bloody nipples, “mama mama mama mama mama” if I shut a door or took a shower, the victory of “getting them down” for a nap so I could write or read or hahahahaha I mean empty the dishwasher and do the laundry and eat cold leftover pasta shaped like rabbits. Almost twenty years later I could not be prouder of my girls, could not be more grateful for the unearned entitlement that allowed me to be so present in their lives (though I regret to inform you that I still haven’t lost the “baby weight” or published a novel). And I wonder every day about what our society demands of women; what we give up and what we gain; how we define and value work; who is allowed choice and who is not; what it means to live a creative life; and of course, am I a good mother?

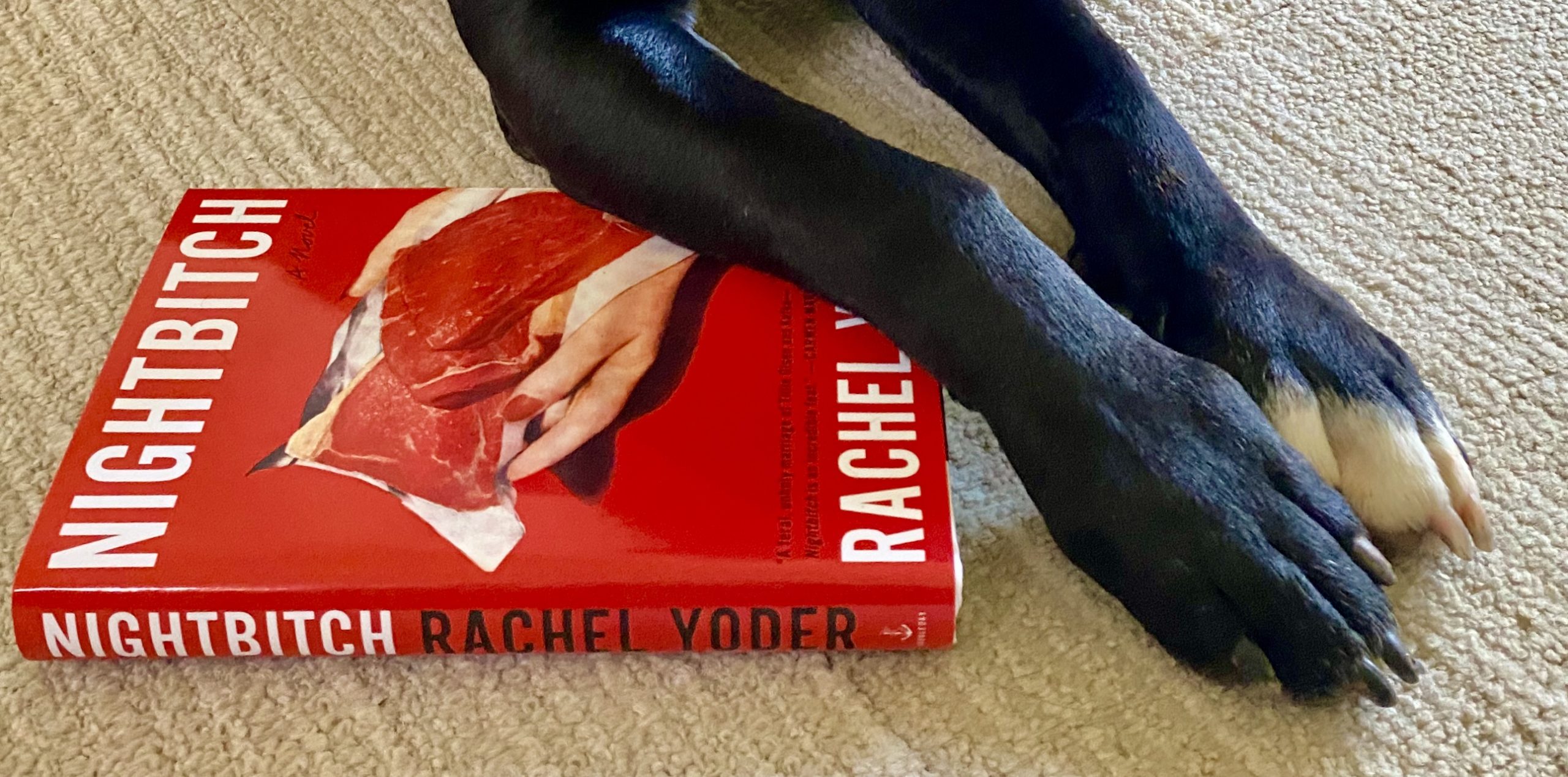

All this to say that perhaps I am the perfect reader for Rachel Yoder’s first novel, Nightbitch. The otherwise unnamed title character is an artist with her dream job in the Midwest who, because her husband makes more money, is the one who leaves work to stay home with her now two-year-old son. The story begins with a patch of dark hair on the back of her neck, her incandescent rage in the middle of the night, and her obsession with a nonfiction field guide to mythical women. We meet this mother—foul-mouthed, funny, chafing, bewildered, enraged—at the beginning of a primal shift: this bone-weary mother, this thwarted artist, is turning into a dog.

What follows is strange, shocking, hilarious, honest, magical. The mother, left alone by her husband with the boy all week, every week, lopes into the night, crafts desperate emails to the elusive author of the field guide, hunts small animals, is befriended by a pack of moms at the library, howls and snarls, meets old friends for a disastrous drink, struggles with the loss of her essential self, and becomes a more present mother as she becomes more canine. One of the central questions of the book is how women’s anger manifests itself: does it consume? does it transform? More specifically, what happens when a woman’s identity as an artist is subsumed by her identity as a mother? Nightbitch is the literal transformation; she is the metaphorical transformation, and she is, it becomes clearer as the book goes on, an actual performance art piece, its content erasing the boundaries between life/art, real/dream, woman/creature. Nightbitch’s performance centers feminine power, the act of creation (of both art and child); it is both Nightbitch and Yoder’s book itself that birth art out of rage. “She had been a girl then a woman, a bride, expectant, a mother, and now she would be this, whatever this was. A wild, complicated woman with strange yearnings. Stubborn and angry—soft and sweet, though, too. She was creator and then also the dark force that roamed the night. She was part high-minded intention and part instinct, raw flight.”

Nightbitch made me laugh out loud, provoked gasps, evoked in me a deep sense of recognition. Nightbitch is my kind of monster. She is my kind of mother.