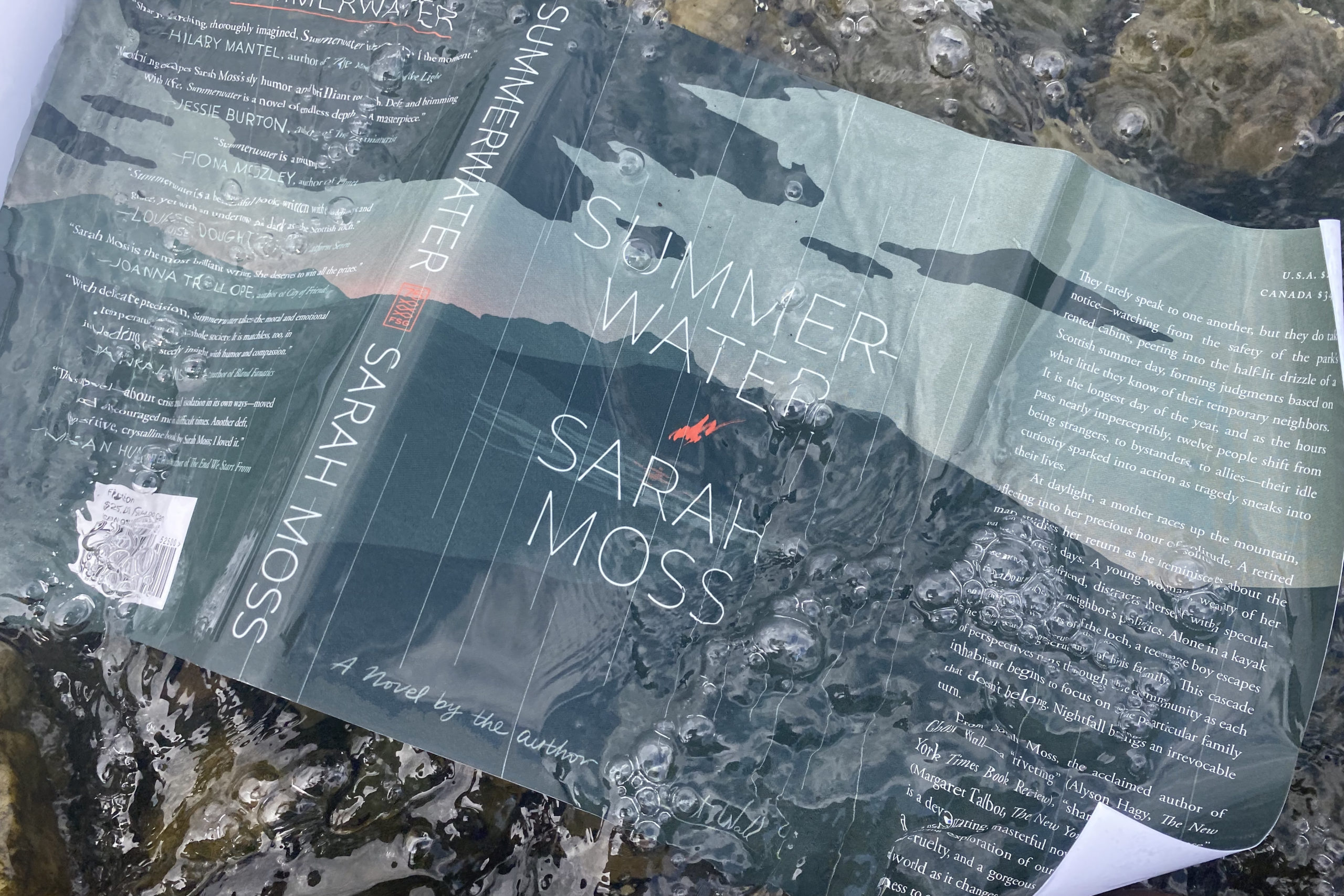

An unrelenting downpour that traps summer vacationers in their shabby cottages on a Scottish loch looms as one of the many characters in Sarah Moss’s short, intense new book Summerwater. From the ancient legend and classic poem that give the book its title, the themes of hospitality, class, retribution, nature’s bond with and alienation from humanity, and the ever-present water reverberate in each chapter focused on a different voice. The alert deer and her fawn, the snarky jogger, the teenage kayaker escaping his family, the cruel child with stones in her pocket, a solitary man lurking in the woods, the sleeping trees, the elderly doctor and his addled wife, a city of ants: all of these presences and more—human, animal, natural—take their turns propelling the narrative of a single day and night that finds everyone watching everyone else from behind rain-streaked windows while the thrum of foreboding builds.

One of the book’s many strengths is the variety of style, the contrast of modern, clever sensibility with a more poetic expression. Consider the juxtaposition of this passage that evokes the drowned world of the source poem: “There are other boats below. There are the bones of skin coracles and the shells of bark canoes and the hollowed-out trunks of trees that once gave shelter to bears. There are the small boats of boys in every century who never came home, and the water holds the hand-stitches of their clothes and the amulets that did not help when they were needed” with the musings of a young woman in pursuit of a simultaneous orgasm with her fiancé: “There should be flags you can raise…like the naval signals her brother still had to learn…You Are Standing Into Danger; Minesweeper On Active Duty; Man Overboard; Actually That Hurts A Bit; This Isn’t Working For Me; Please Get On And Finish Now…I’d Rather Be Reading; I’m Too Full of Dinner.”

Moss has an acute sense of how people delude themselves, how our prejudices and vanities and desires are both heartbreaking and humorous. Every section introduces danger—a weak heart, a speeding car, a teenage rage, a missing girl, a sudden storm surge—and there are intertwining symbols and repetitions that echo through the book in an unsettling refrain. Though they stay separated, judging, most of the vacationers are angered by the loud music coming from the “foreigners’ cabin” where a noisy party rages. The varying degrees of racism, curiosity, envy, rage, and eventually, convergence, reveal Moss’s talent to locate universal themes in specific, familiar people in such concise sections. I read Summerwater in one go, eagerly turning pages and admiring the writing all the while, but weeks later, it is the aftereffects of the events, in all their terror and hopefulness that stay with me, and the almost unworldly atmosphere that merges saturated sky with deep lake.