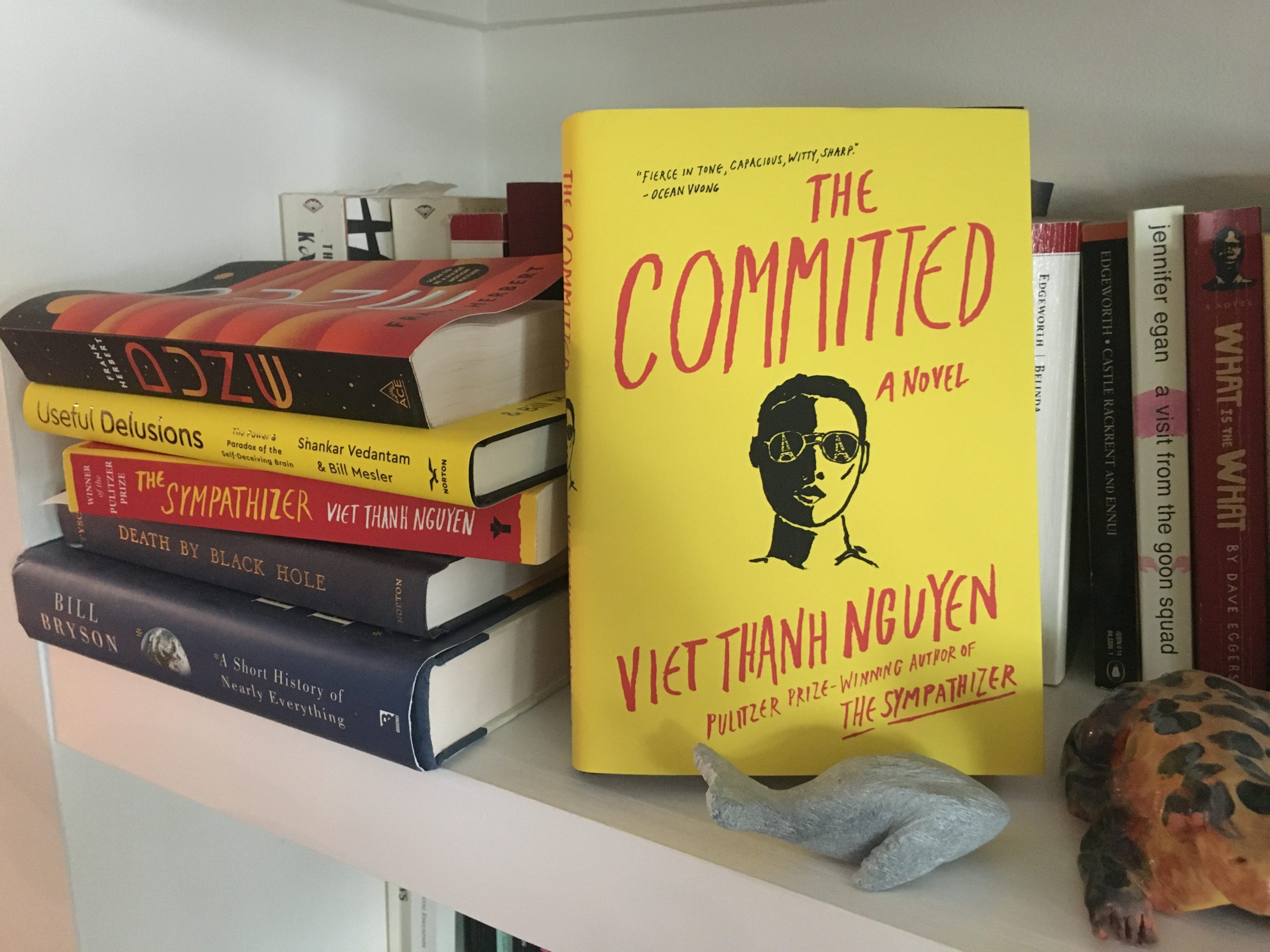

One of the best books I read in the last few years was Viet Thanh Nguyen’s ferocious, hilarious, and brutal debut novel, The Sympathizer, which snapped up prizes left and right, including the Pulitzer. In it, Nguyen’s exuberantly maximalist unnamed narrator, a Vietnamese-French communist double agent pretending to be a member of South Vietnam’s military intelligence, is sent by his handler to the US to continue spying on refugees who may be planning one more counterstrike. But the plot, despite its fun and chaotic twists and turns, is secondary to the novel’s true nature—a funny, savage, and unflinching satire of US pieties about the Vietnam War.

This year, Nguyen published The Committed, a sequel that flings our hero to early 1980s Paris, fresh off a stint in a vicious Vietnamese reeducation camp. Where the first novel’s analysis of America’s patronizing racism was grafted onto a double-agent spy thriller, the new novel is a raucous, finger-pointing takedown of French colonial history in Vietnam, layered over an often cartoonishly outré gangster story. Now going by a moniker that means “No Name” in Vietnamese, the narrator joins a gang of Asian drug dealers whose baroque self-mythologizing echoes that of the French leftist intellectuals whom he supplies with a narcotic only known as “the remedy.”

Conflicts of identity are inescapable, and every character is living some version of double consciousness, from the brothel bouncer elucidating the Martinician philosopher-poet Césaire, to the gangster fusing three cultures to name himself Le Cao Boi, to amateur criminals asserting their Algerian-immigrant alienation while taking offense at not being called French. These divisions of the self are most pointedly embodied by the three blood brothers at the center of the novel: Man, Bon, and the narrator. Man, the literally faceless communist, no longer claims any identity at all. Bon, the single-minded, bloodthirstily moral killer of communists, is the most fully committed of the novel’s many ideologues. And our protagonist’s splintered psyche tries to reconcile white and Vietnamese, communist and republican, socialist and capitalist.

The Committed delighted me on so many levels. There is joy in watching Nguyen experiment with form and play with language and register. His tone mixes anger, wry detachment, and bitter mockery. His style shifts often: clipped staccato sentences syncopate a nightmarish scene of Russian roulette; later a four-page long sentence unwinds the shifting power dynamics of a stickup going awry. The plot meanders through a series of imaginative set pieces and culminates in an orgy scene straight out of some kind of post-colonial Rabelais, in which rich white men enact colonial power stereotypes on the bodies of the women paid to represent subjugated nations. The novel parses the colonial subject’s conflicting impulses towards its colonizer, arriving at a stalemate that, in the narrator’s words, amounts to “Thank you! Fuck you!” repeated ad infinitum. Roiling with disgust but happily playing in filth, furious but compulsively readable, this novel is a kick in the teeth that’s also a knowing, resigned shrug.