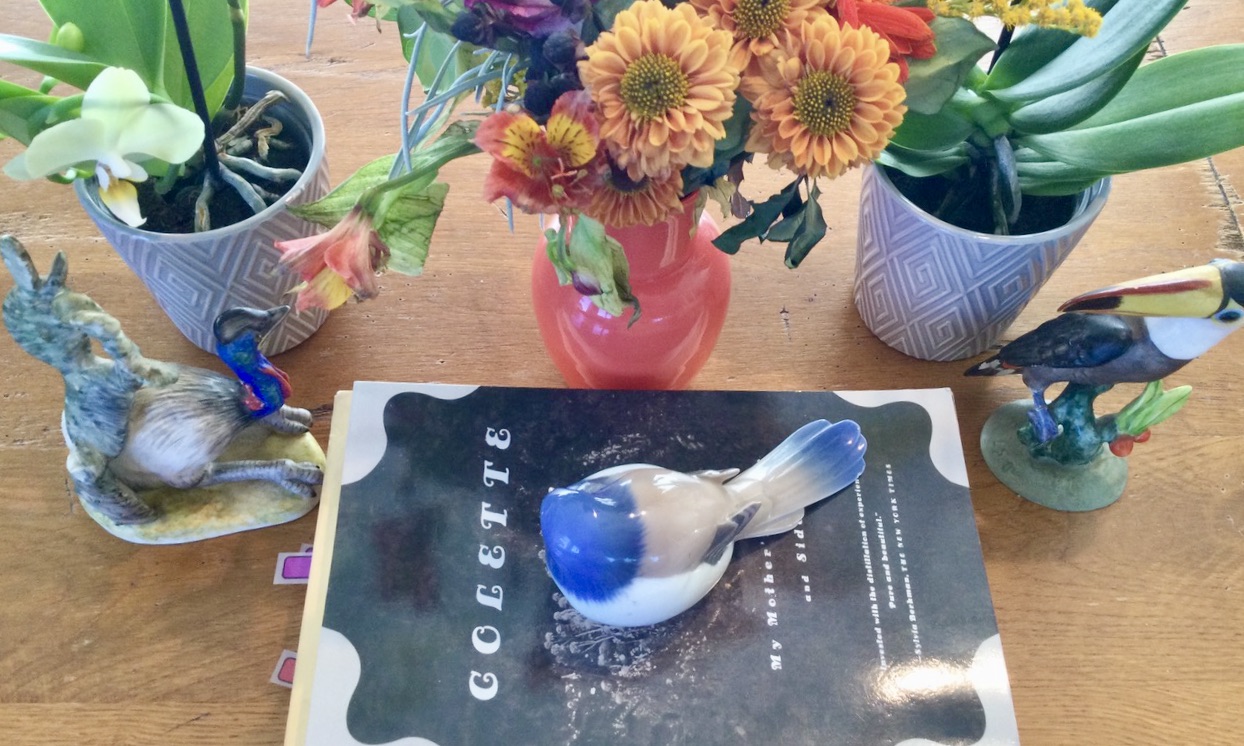

During this season of lonely holidays I found Colette’s My Mother’s House to be a wonderful antidote to our covid-centered present, whisking me back to an earlier, simpler time in rural France. Colette — mime, actress, journalist, and prolific author — captures her childhood and country life in Burgundy in clear, simple and passionately vivid prose that’s a delight to read. Gide agreed, telling Colette, “With what intelligence, mastery, and understanding you have taken up the least-admitted secrets of the flesh… there is not a word which does not count.”

My Mother’s House is a non-linear account of Colette’s family, viewed through the prism of the backward look and focusing on her mother, Sido. Here, Colette recalls the feeling of her mother’s protective presence when she was a child of eight:

Nine o’clock; summer; a garden looking larger in the evening shadows; rest before sleep. Hurried steps on the gravel from the terrace to the pump, from the pump to the kitchen. Sitting close to the ground upon an uncomfortable little foot-stool, I rest my head, as I do every evening, against my mother’s knees, and guess with my eyes closed: “That’s Morin’s heavy step, on his way back from watering the tomatoes. That’s Melie emptying the potato parings. A little high-heeled step: here’s Madame Bruneau come to have a chat with Mother.”

With the instinctive evocation of the drama of early evening, Colette calls back a frozen moment of perfect peace in the garden at nightfall evoked by the security of her mother’s touch and the predictability of neighbors’ daily routines. The senses conspire to create a specific word-picture that might evoke similar moments we’ve experienced with our own mothers or caregivers at moments of perfect peace, though our settings may be different.

Writing long after childhood in language that’s lyrical, nostalgic, precise, but never sentimental, Colette writes in middle age to memorialize her mother, a formidable country woman who could read Nature’s signs and kept a firm hand on not only her children but her neighborhood as well. A powerful presence in her daughter’s life, Sido was funny and opinionated, outspoken and determined. She possessed folk wisdom which she passes on to her daughter, such as how to read the layers of an onion at harvest to predict whether winter would be harsh or mild. Here, the force of the writing derives from its appeal to the senses, its clarity, simplicity, and the passion that lies beneath her descriptions to express her love for her formidable mother:

My mother smelled of laundered cretonne, of irons heated on the poplar-wood fire, of lemon-verbena leaves which she rolled between her palms or thrust into her pocket. At nightfall I used to imagine that she smelled of newly-watered lettuces, for the refreshing scent of them would follow her footsteps to the rippling sound of the rain from the watering-can, in a glory of spray and tellable dust.

Memory is tricky, and the narrator may or may not be reliable. But does a memoir have to stick to the facts in order to be true? In contrast to fiction, a memoir is an interpretation of life, and therefore produces ambiguity. It tries to confront the space between fact and memory, and at the same time to tell a compelling story. It represents not “The” truth, but “A” truth. Colette’s version of her mother’s life raises questions about her veracity, but we are held captive nonetheless by her sensuous writing and the incipient drama of her memories:

In the failing light I remain leaning against my mother’s knees. Wide awake, I close my useless eyes. The linen frock under my cheek smells of household soap, of the wax that is used to polish the iron, and of violets. If I move my face a little away from the fragrant gardening frock, my head plunges into a flood of scents that flows over us like an unbroken wave: the white tobacco plant opens to the night its slender scented tubes and its starlike petals. A ray of light strikes the walnut tree and wakens it; it rustles, stirred to its lowest branches by a slim shaft of moonshine, and the breeze overlays the scent of the white tobacco with the bitter, cool smell of the little worm-eaten walnuts that fall on the grass.

For another view of Colette’s life, read Judith Thurman’s marvelous biography, Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette, the perfect companion to this charming memoir.