How does a writer heal the deepest wounds of her life? The shattering loss of her beloved mother to violence and the pain of being born Black in America, particularly in the South, merge with profound meaning in Natasha Tretheway’s near-perfect book, Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir. In the shadow of Stone Mountain, where massive monuments of Confederate generals loom, Tretheway’s mother Gwen was murdered by her ex-husband (Tretheway’s step-father) when Tretheway was nineteen years old. Memorial Drive joins downtown Atlanta to Stone Mountain, linking racist present to racist past, linking veneration of history with its terrible losses and reverberations, linking Tretheway’s private wrenching need to memorialize her mother with the public reckoning of what it means to be Black in America. Above all, this is a poet’s memoir, as contained and fierce as banked fire. The title of every short chapter works in myriad ways; Tretheway examines photographs and dreams with an artist’s eye; and she weaves mythology, recurring images of thresholds and doorways, numbers, and visions to create a haunted, haunting story, one that incorporates the specificity of language and intensity of metaphor effective in poetry.

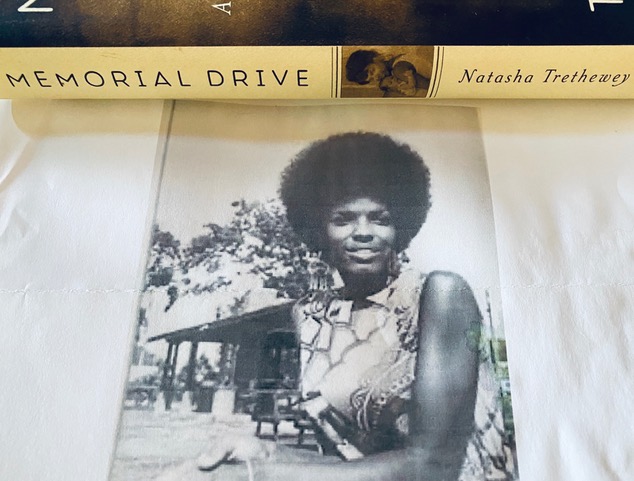

Tretheway’s 1966 birth in Mississippi is “illegitimate,” though she remembers a warm, loving childhood marked by incidents of racism and the growing separation between her illegally married parents, a white professor/writer and a Black professional mother. Tretheway explains that she has suppressed the years she lived in Atlanta with her mother and her stepfather: “In my attempt at willed forgetting, I would collapse the distance between bookends, the year that ended the world of my happy early childhood pressing right up against the new world I’d entered suddenly as a motherless child.” In articles after she won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and became the US poet laureate, Tretheway noticed that her becoming a writer was often attributed to her father’s encouragement and career while her mother was relegated to a tragic footnote. In order to tell the story of her mother’s vital role in her calling, Tretheway must pull apart the bookends and delve into the defining trauma of her life.

In telling the story she has repressed for so long, Tretheway is also defining her own creation myth: the death of the mother and the birth of the writer. She gives her mother a voice by including her written accounts and a long transcript from a terrifying phone call with her murderer recorded a few days before she died. In these difficult sections, we read verbatim Gwen’s exhaustion and fear and courage in resisting relentless, foreboding abuse. Memorial Drive is as challenging and rewarding as analyzing poetry; it is worth reading more than once. In her own courageous examination of memory, Tretheway’s metaphor of phantom pain, one felt for a missing limb, emerges as a way to memorialize her mother, whose heart beats beside her daughter’s, both achingly absent and deeply present.