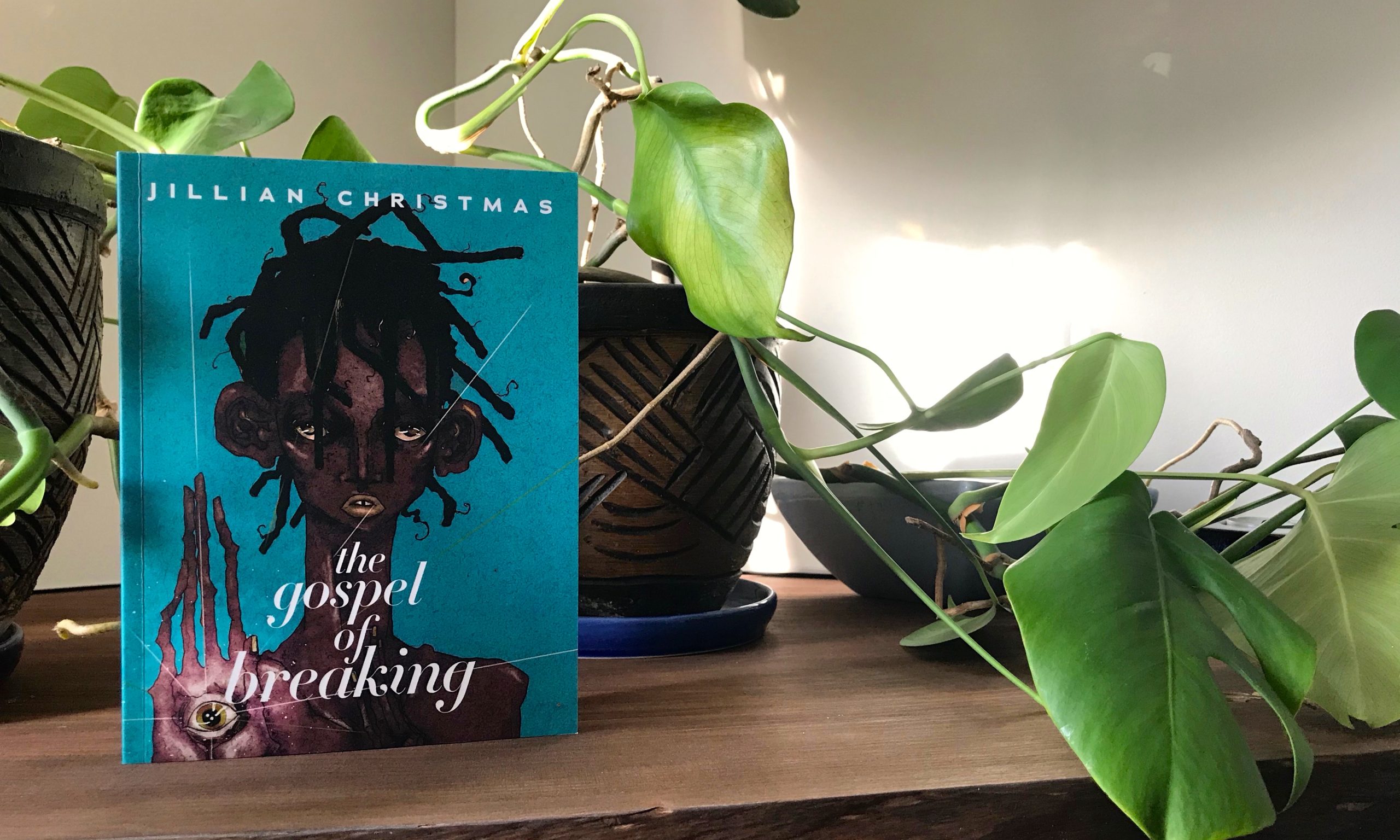

There’s a bit of a lead-up to my book review. I apologize a little, but not much. In the context of these times we’re living in, and with my brain so full of questions and confusions and ideas, the preamble helps me to place the importance of reading books like Jillian Christmas’s The Gospel of Breaking, even if, as I’m sure some of you would agree, poetry can be tricky.

I am not a poet. Nor am I someone who frequently reads poetry on my own. Nor would I say I’m someone who is particularly adept at understanding it—not without some work, anyway. I can teach poetry to young people—help them appreciate it, get inside of it, wonder about it. I can do that enough that I feel pretty good about what I’m offering them when we explore poetry together. But even as an English teacher, I find poetry challenging.

These past few weeks have been exhausting and sad and hard. Less hard for me than for some folx, to be sure, but still hard. I’ve been reading and watching and listening to so much information—narratives, non-fiction, news, manifestos, guides—trying to learn more and be better. And in one of those ‘texts,’ a podcast about the limits of an anti-racist reading list, writer Lauren Michelle Jackson talks about how so many of these lists include great literary works by names many of us know—Morrison, Baldwin, Lorde—but when we turn to these kinds of texts as a window into ‘how not to be racist,’ we ignore their craft and reduce them to some kind of “roadmap to racial awakening.” She goes on to differentiate between reading for urgency, for a desperate knowledge of racism, injustice, history, etc. versus reading literature written by Black writers to appreciate the writing itself—the form and words so carefully constructed on the page. And she points out how this second type of reading takes time—it’s not meant to present us with a ‘how to,’ like many of the non-fiction books on these lists. So, she says, we must ask ourselves, why are we reading what we’re reading right now? For what purpose?

I guess with those questions in mind, as well as with a sense that, in those particular moments, I didn’t want information but rather a pause from the urgency and desperate grasping for information I’ve so immersed myself in these past weeks, I picked up Jillian Christmas’s book of poetry, The Gospel of Breaking. Christmas is a queer, Black, spoken word artist and writer whose work I know from local slam poetry nights and literary festivals. When in the same space as her, it’s impossible not to notice the abundance of her spirit, her warmth, her powerful commitment to community. And so I knew her poetry was the right choice for the moment.

The Gospel of Breaking is a testament to Black bodies, to motherhood and grandmotherhood, to queerness, to the religion of love and sex, to the countries of our past and present, to memories and forgetting. Christmas’s poems about her mama and her mommy—her mother and her grandmother—pulled me in the most, the brown hands and mangoes and motherly judgement/protection a kind of cushion. As I read her poem “things I can do (for Sylvia)” I found myself not wanting it to end. Something in the kind of love expressed, the deep care of a loved one as they lay dying (“I can…rub ponds into the whisper-thin / creases of you. / I can watch and wince / as nurses change / another diaper”)—being in the presence of that kind of love was comforting and I wanted to stay there. And then there’s the utter sweetness of the first section of “what forgetfulness is for,” which takes a potentially disturbing act and offers a gentle and hopeful re-interpretation of this act, at which point I let loose an audible “AW.” Along the way, poems like “hard to tell if this is just the internet, or another dream where I am in front of the class in only my dirty underwear” and “the bike poem” made me cringe and laugh out loud—just another way Christmas holds you in her generous hands (“douche-canoe” remains one of my favourite new words). Christmas’s poems toy with many forms, sometimes prose-like, sometimes reversing their words across the page, often-times spacing themselves out in a kind of luxurious stretch—like an invitation to yawn and fling a leg over the edge of the bed.

In allowing myself the space and time to sink into the fortifying gospel of Christmas’s words, I not only re-filled my little brown soul to fight a-fresh another day, but was reminded of how much beauty and nourishment you can find in being a little lost, of not having information and stories fed to you plainly and unmistakably. As Christmas lays out in “northern light”:

some think the dark is full of terrors

because they cannot see

what it conceals or perhaps

they do not know that the dark itself is

a precious gift and we

strange creatures of the shimmering

north can be the light that it reveals

So much is terrifying right now, so much is confusing. But perhaps if we allow ourselves to wander a little, to take our time and be gathered in by some of that precious darkness, we might find those shimmering points of light. Christmas’s words are a good place to start.