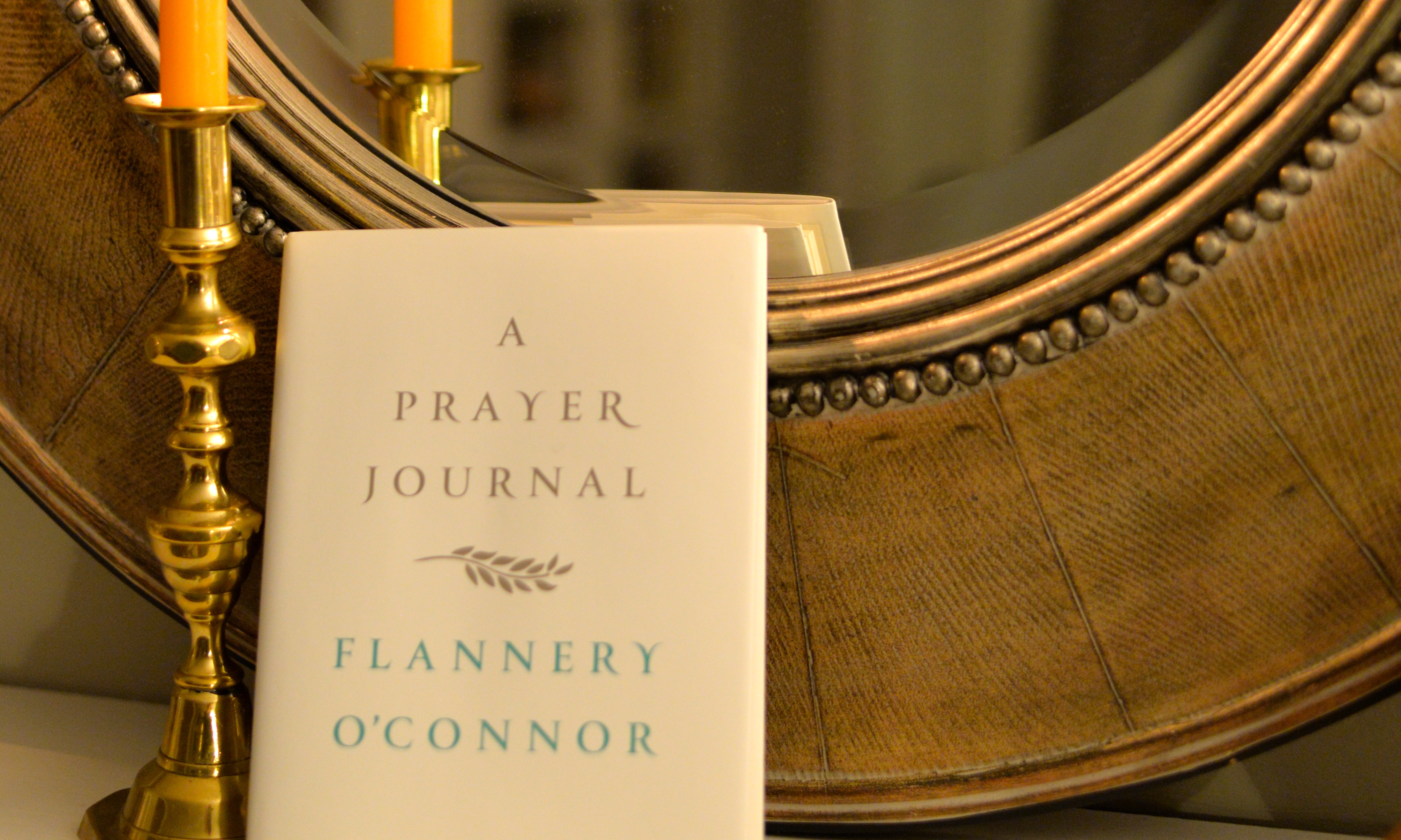

I first heard of this book while reading Sarah Ruhl’s Letters from Max, because she recommended it to her dying friend. I assumed it was an O’Connor text that I had somehow missed during the past two decades of my admiring this Southern Catholic writer. Not so. The prayer journal was discovered among O’Connor’s papers in Georgia only a few years ago. I immediately ordered a copy.

O’Connor kept the journal while a graduate student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and though a scant 40 pages she packs each entry with pathos, wisdom, and humility. At first, the very act of reading the entries seemed uncomfortably voyeuristic. After all, what could be more intimate than someone else’s deepest desires from their early twenties? But as I read on, I found myself so delighted by her familiar gifts of profundity and humor that it felt more like a conversation with an old friend than an intrusion. In one entry she prays: Give me the grace, dear Lord, to adore You with the excitement of the old priests when they sacrificed a lamb to You. And she later claims: Today I have proved myself a glutton––for Scotch oatmeal cookies and erotic thought.

O’Connor often prays for an increase of faith: God is feeding me and what I’m praying for is an appetite. She aims for nothing less than Divine union (like the Christian mystics, or like John Donne), but first she knows she must desire that union: Dear Lord, please make me want You. It would be the greatest bliss. Not just to want You when I think about You but to want You all the time, to think about You all the time, to have the want driving in me, to have it like a cancer in me. It would kill me like a cancer and that would be the Fulfillment. Her fervor for divine consummation is deeply edifying to read in these troubling times, when so much fervor seems to be rooted in resentment, in rage.

It is also clear from these prayers that, like so many artists who came before her (but like so few since), O’Connor longed to be God’s hand, for her words to lead others to the Word. Over and again she prays that she will be inspired with new stories, that they will find published success, and that they will be authentically, transformatively Christian: Please help me to be an artist, please let it lead to You.

Several years ago I took a group of students to Andalusia, O’Connor’s family home in Milledgeville, GA. We wandered around the house and property and observed her typewriter and tchotchkes, her porches and peacocks. These were the spaces where she, burdened by lupus, would be her most prolific, producing the short stories and novels that would eventually cement her reputation. There was a distinct sadness in the air, wafted I’m sure by our knowledge of her suffering and early demise. But this journal reflects a time before any glimmer of fame, before her fatal diagnosis, when her future must still have seemed full of possibility. It is deeply beautiful and––astonishingly––hopeful.