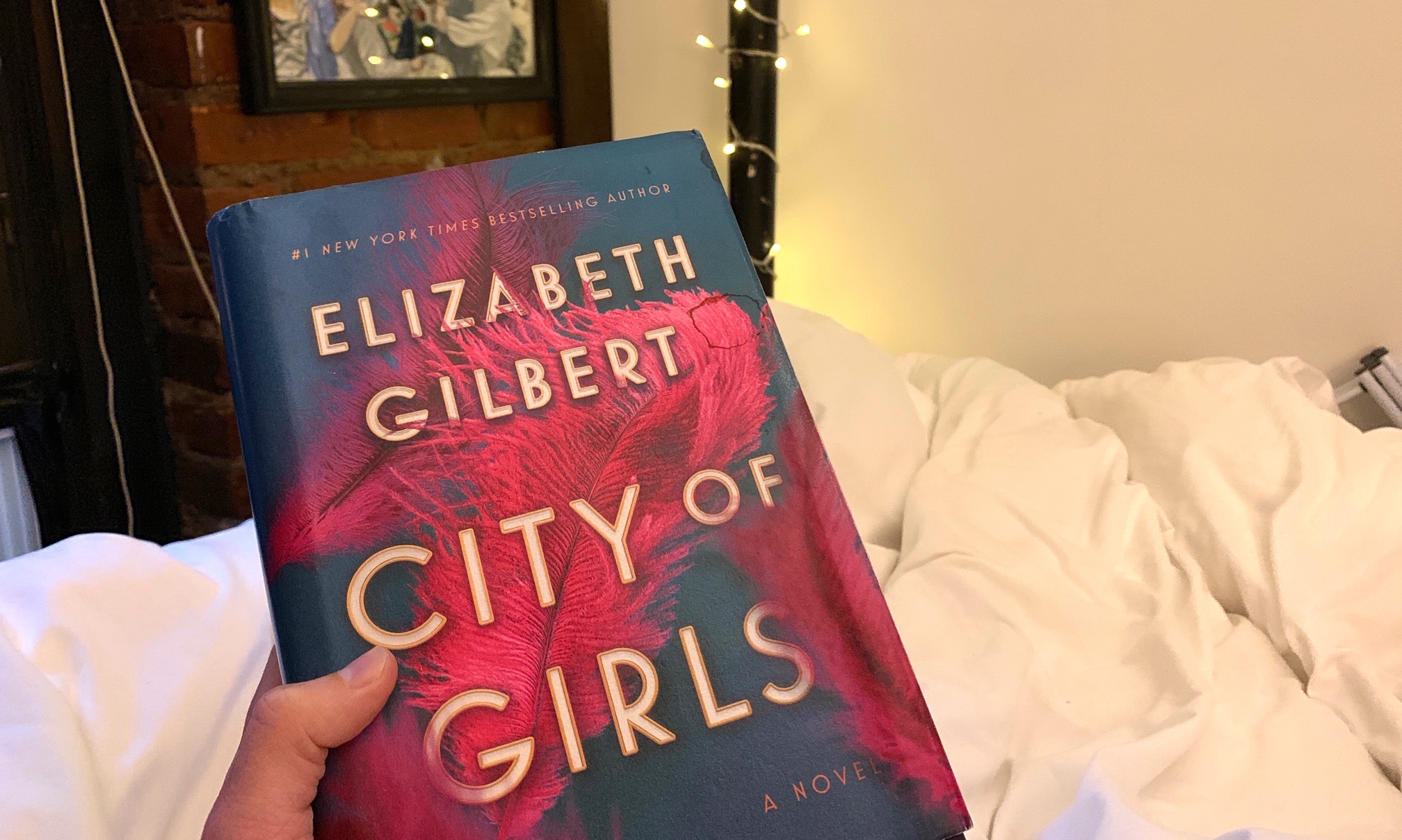

In Elizabeth Gilbert’s newest novel, City of Girls, her heroine’s journey is far from the author’s own biographical Eat, Pray, Love story of zen and exotic indulgence. Gilbert’s new book, which takes its form as a letter written in the hand of the now elderly Vivian, reflects back on Vivan’s youth spent in New York City and her search for meaning outside of college, “proper” society, work, and marriage. At the beginning of the novel, we meet a moody, frustrated chameleon. But by the end, Vivian has become an incredibly interesting person. And the men by her side? Nothing more than nameless boys, disappointing actors, and ghosts. She stands tall on her own. Ultimately, City of Girls follows Gilbert’s favorite theme of a woman who finally falls in love with herself.

Despite this book’s divergences from Eat, Pray, Love, the escapades of a 19-year-old Vivian do bear their own distinct descriptions of consumption, awakening, and passion. Vivian drinks and dances away her first years in the city, joins the religious order of the theater, and loves her way through all the nightclubs east of the Hudson. Even though Gilbert presents her main ideas through a fictional lens, she once again uses similar elements to show the very real struggle of a woman trying to find and define herself outside of social norms.

At first, I found myself frustrated by the reverence Gilbert places on the twinkling socialite and her life in the city. But then I considered the format of the book itself: for all intents and purposes, it is a letter (a very, very long one) written by a woman in her nineties to a younger woman, so it makes sense that the narration carries with it the flourishes and rosy memories that an elderly person might impart to a younger listener. Reading the novel, I almost felt as if I were listening to my Nam talk about her days growing up in Memphis, and I forgave Vivian her extravagance.

The book is conscious of its own cliches, often pivoting just enough to merely brush up against convention without stumbling headfirst into it. Vivian says and does exactly what we don’t expect her to. Just when we think we have figured her out, she changes. Just when we think she will never mature, she stands her ground, or makes the hard decision, or apologizes. And when we think she will fall in love, she does — and she doesn’t.

I found that I actually liked Vivian, who is dynamic and predictable, frustrating and understandable. Gilbert’s writing allows Vivian to live and breathe like the flawed woman (human) that she is. Or maybe I was drawn to her because she presents herself as the Scarlet O’Hara of 1940s New York. Vivian isn’t actually that likable — she’s a spoiled society girl who can’t find the time to be interested in school, long-term relationships, or a career. She complains and drinks too much. But she is also successful and smart. She rises from the ashes of her own undoing and refuses to apologize for the person she is. The plot itself is, for the most part, blissfully free of the self-deprecation and guilt that can be mainstays of stories about girls comfortable with their sexuality in the pre-WWII era. And in that way, Gilbert quietly skirts the cliches this genre and subject usually bring.

In City of Girls, Gilbert bridges the gap between 1940 and 2019. Vivian began to feel less like a crusty relic and a whole lot more like a Gen Z-er. I enjoyed hearing her talk, so I listened. Her brazen divulgence of wild nighttime escapades and early morning hangovers felt all too similar to the stories my own friends tell me over Sunday coffee, mascara smearing the corners of their eyes.