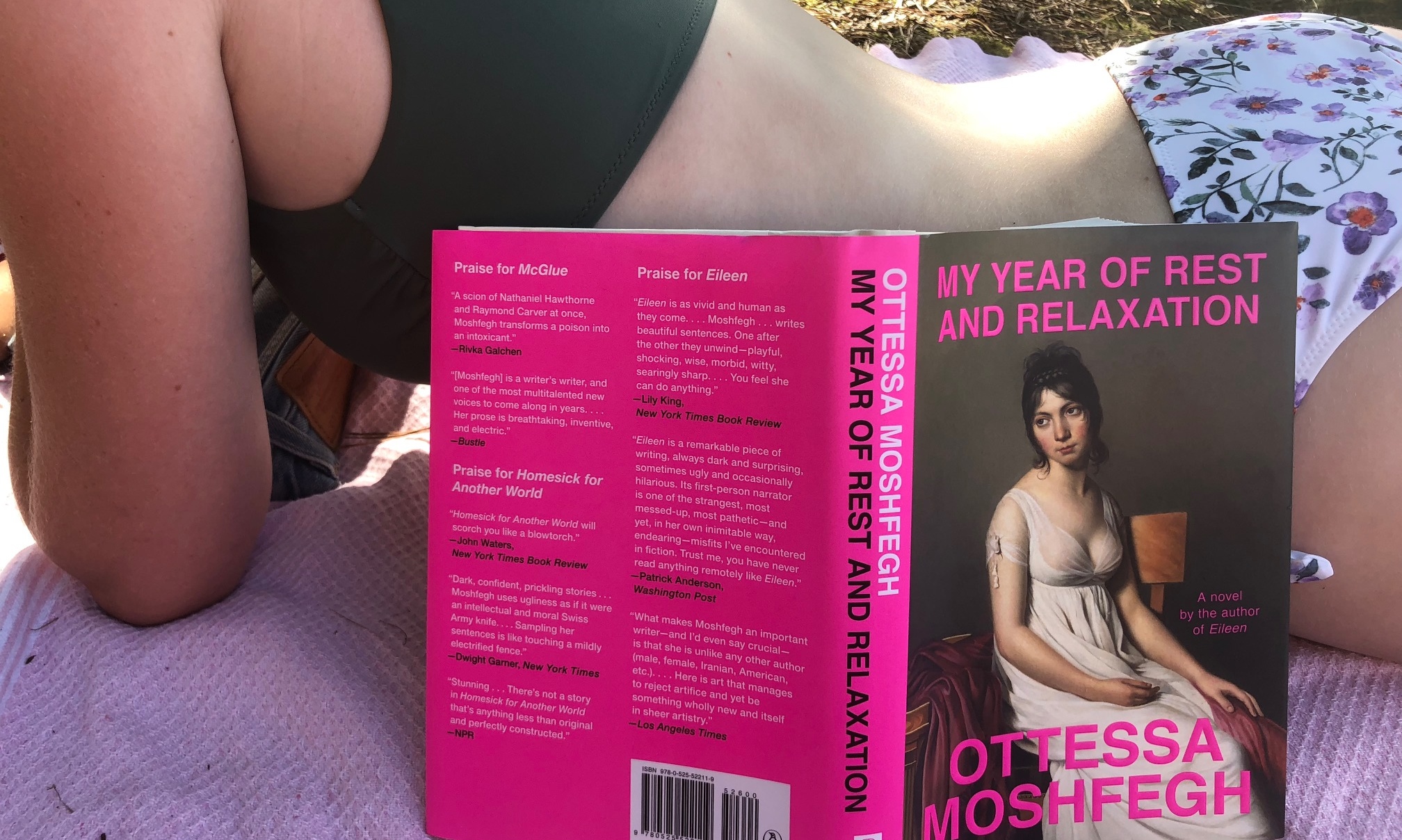

a bookclique pick by Jessica Flaxman

Like the narrator of Ottessa Moshfegh’s laid beau (ugly, beautiful) novel, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, I lived, worked, and tried to sleep well in New York City from 2000-2001. Getting a good night’s sleep was hard because there was so much to keep me up at night. The woman who lived upstairs refused to put down rugs and her dog barked constantly; buses idled on the street just below my bedroom window; my mind whirred, powered by the adrenaline and anxiety of being a new teacher, a newlywed, a New Yorker. I was 27.

For Moshfegh’s nameless 24 year old narrator, the reasons she can’t sleep are more profound, although she is not able, for most of the book, to effectively plumb her depths. After losing both of her parents, graduating from Columbia, and launching into adulthood without a partner or a good enough job, aimless and untethered, she takes an arsenal of sleeping medication to avoid thinking. Probably because she is white and has plenty of money, a healthy body, and a beautiful face, she is able to navigate a universe of anguish – and sometimes insanity – largely undetected and wholly unhelped. Her prescribing doctor seems to be a sympathizer on the one hand and a sadist on the other, and maybe, ultimately, a psychopath.

It’s scary and fascinating to watch a person with everything going for her try so hard to quiet her mind, yet not die. She eats just enough, moves just enough, communicates with the outside world just enough to hang on. Most of the time, she is truly unlikeable – someone who lacks empathy for others, lies, forgets, borrows, and steals, is inappropriate in her thoughts and deeds – but she is also pitiable, a young woman for whom no one seems to really care, including her best friend, her employer, her doctor, her lawyer, or her doorman. She’s the woman in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper; she’s Gregor in Kafka’s Metamorphosis; she’s Edna Pontellier in Kate Chopin’s The Awakening; she’s Girl, Interrupted; she’s everyone and no one at all.

Infermiterol, a made-up drug, finally does the trick of rewiring and relieving her mind. When she takes it, she loses three full days of her life and remembers nothing of those days when she wakes up. The reader can’t help but compulsively read as the narrator discovers, through purchases, messages, and changes to her body, what she’s done in the missing three days. In order to completely erase her past pain and start anew, she takes an Infermiterol every three days until she’s used up her supply of 40 pills. At the end of the 120 days, she wakes up and renews her life and on September 11, when the Twin Towers hurtle to the ground and the book ends, she is fully conscious.

Moshfegh’s book kept my attention all the way through, but during the last quarter, I found myself reading furiously. It was as if I was aware of a dream, or a nightmare, that was ending, and I wanted to capture something of what it was about, and knew that I probably would not. As the book closed, I was surprised by the tears streaming down my cheeks, having relived, to some degree what the time that ended with 9/11 was like for me when I was a young woman, for New Yorkers, for the country, and maybe the world.

The experience of reading the book, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, was neither restful nor relaxing, but like a nightmare stitched into a dream, it continues to haunt.