“Imagine, the letters one has sent out into the world, the letters received back in turn, are like the pieces of a magnificent puzzle, or, a better metaphor, if dated, the links of a long chain, and even if those links are never put back together, which they will certainly never be, even if they remain for the rest of time dispersed across the earth like the fragile blown seeds of a dying dandelion, isn’t there something wonderful in that, to think that a story of one’s life is preserved in some way, that this very letter may one day mean something, even if it is a very small thing, to someone?”

–Sybil Van Antwerp in The Correspondent

I love imagining all the letters that have been sent into the world across centuries, the “magnificent puzzle,” the scattered fragile seeds, the bundles of letters tied with string, tucked into drawers or trunks or desks waiting to be discovered, re-read, scrutinized.

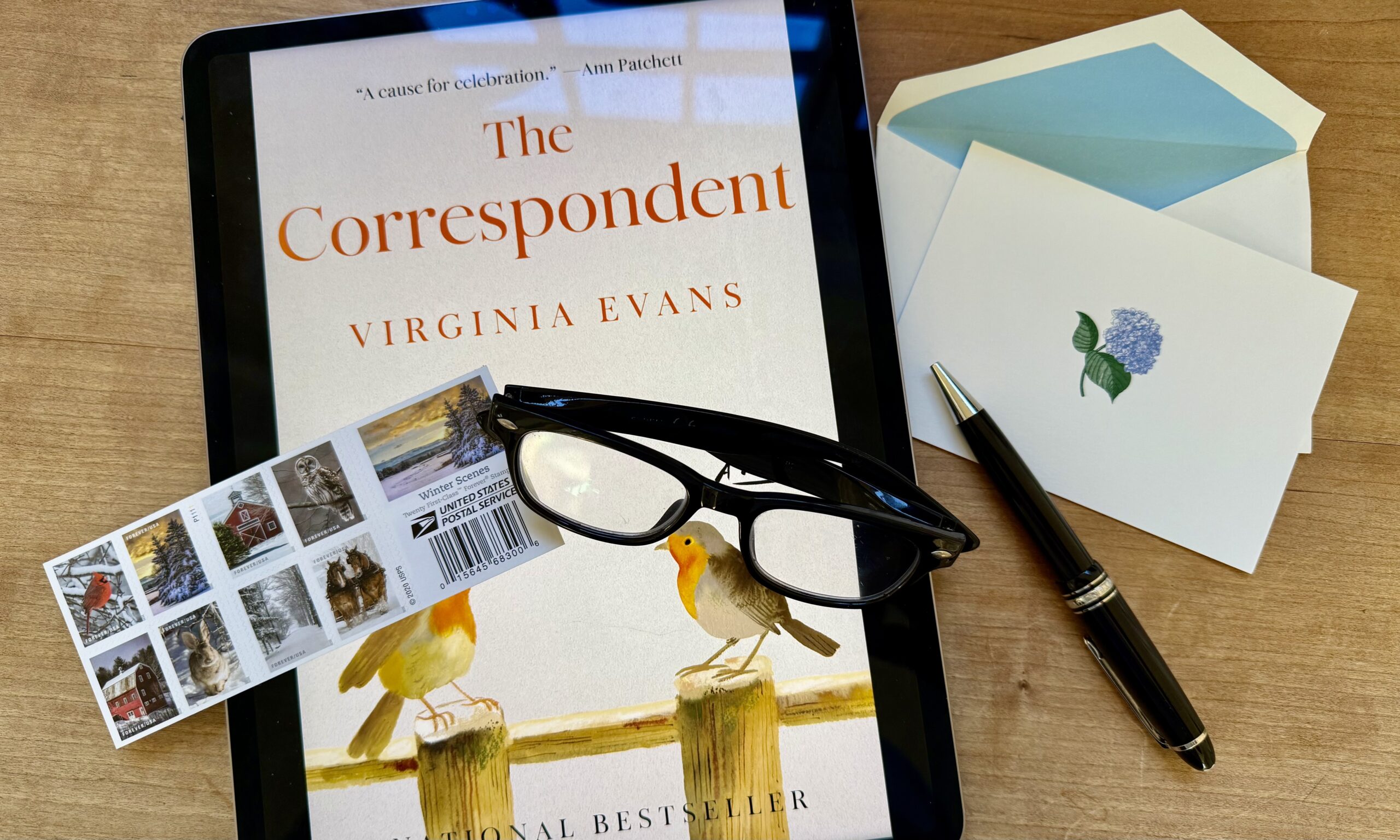

Last spring, everyone told me I had to read Virginia Evans’ debut epistolary novel, The Correspondent, which I finally did–and I listened to it, too–the audio version is wonderful! Enchanted by the well-constructed plot, each character’s distinct voice, and the exquisite articulation of long-held grief, regret and possibility, I never wanted the story to end.

Sybil Van Antwerp, the irascible, rigid, marvelous heroine of The Correspondent, inspired me to resume my own letter-writing practice, and I imagine she may have that effect on the many readers who, like me, fall a little bit in love with her.

Growing up, my childhood was peopled with Sybils–older women whose hairdos had been sprayed into submission, who carried purses that snapped shut and wore sensible shoes. But Sybil of The Correspondent is more than her prim exterior suggests. She is tough, even cantankerous, but we learn as we read her letters that she is also vulnerable, compassionate, willing to accept responsibility for her actions, and, ultimately, admirable.

When the world feels out of control and our own lives feel precarious, we control what we can control. Sybil confronts her impending blindness (both literal and metaphorical) by adhering to her life-long practice of writing letters to make sense of her world.

An epistolary novel is an old-fashioned form, and this story is carried forward by the correspondence Sybil sends and receives. I appreciated how we hear about Sybil’s life through the hints others drop about her–her best friend, her ex-husband, her marvelous neighbor, the kind man who works at the mail-away DNA company, the socially awkward teen who trusts her, her estranged daughter–all of them help Sybil emerge as much more than a buttoned-up scold. Evans assumes we can figure out the missing pieces of Sybil’s story, and eventually our patience is rewarded as we learn all we need to know. Evans trusts her readers. Sybil’s past is not simply laid before us like a breakfast buffet; we must put it all together, as she does, letter by letter.

Sybil–stubborn and irritating and wounded–has a bit of the philosopher about her. In her 70’s, she is able to see more clearly, even as her sight diminishes. As she looks back on her career as a law clerk and young mother, mourning the sense of purpose that that time in her life offered, she notes, “I didn’t know it was happiness at the time, because it felt like busyness and exhaustion and financial stress and self-doubt.”

Reflecting on her failed marriage, she writes, “Grief shared, I think, can produce two outcomes. Either you bind yourselves together and hold on for dear life, or you let go and up goes a wall too high to be crossed.” Sybil builds high walls, but what satisfaction we feel as those walls crumble!

Letters, I fear, are a vestige of another era, one in which communication moved more slowly, one in which we took time to fill our fountain pens and write pages and pages in loopy cursive or tight print. One of my grandmothers often wrote sideways on the margins of the letters to her family, wasting not an inch of paper. After I finished The Correspondent, I went to my desk and wrote several long overdue letters–on stationery in ink with stamps. I wanted to re-connect with old friends, to offer sympathy, to reach out to people with whom I had lost touch.

Evans creates a world that we inhabit with Sybil, and, I suspect, many of us will write more letters once we finish this splendid book.