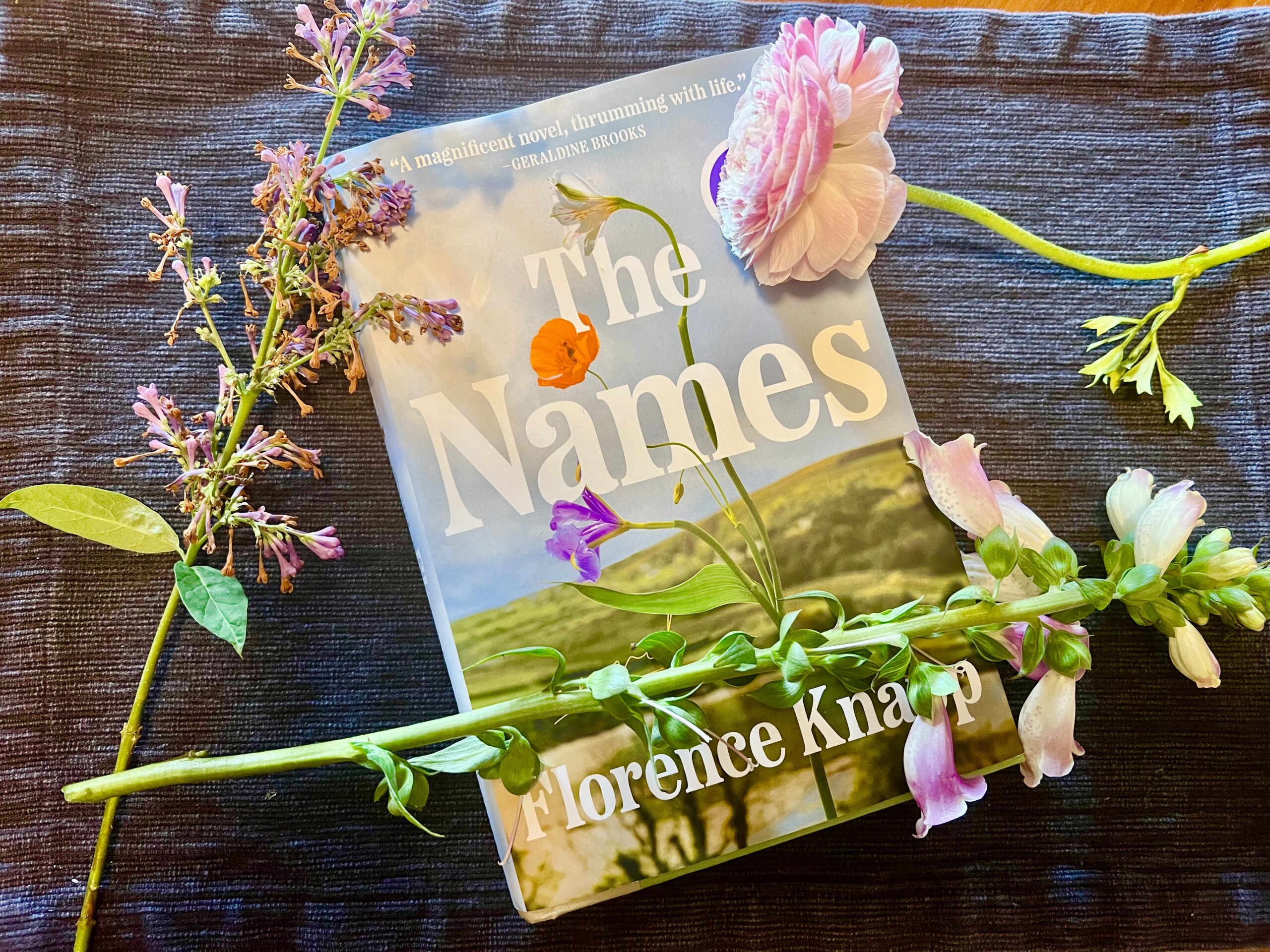

It’s 1987 and a young mother, Cora, walks through an English town with her newborn son and her nine-year-old daughter Maia to register his name. Will she follow the tradition of her abusive husband’s family and name her son after his father, Gordon? Will she find the courage to register him as Julian, the name she prefers? Or will she throw caution to the wind and choose Bear, Maia’s choice, as it sounds “soft and cuddly and kind…but also, brave and strong”? In the following section, Florence Knapp’s inventive novel, The Names, splits into three chapters, one for each choice. For the rest of the book, every section jumps ahead seven years and follows Cora’s son as he moves through the world named Gordon, Julian, or Bear. Each trajectory is informed by devastating domestic violence as Cora reaps the consequences of her decisions, Maia’s self-knowledge is quick or slow to flower, and every version of the boy grows to adulthood bearing the burden and power of his particular name.

The Names raises philosophical questions about the life-altering results of seemingly minor decisions; it asks us to ponder the role of fate and free will and the importance of how our parents choose to define us and how we self-identify as the result of our names. Does the joyfully wild child Bear experience freedom that leads to happiness or does his carefree nature prolong his inability to settle down? Will cautious, artistic Julien protect himself from pain or will he learn to process loss so that he can experience love? Is it inevitable that Gordon, his father’s namesake, will be consumed by a legacy of violence or is it possible to overthrow that story and pursue a healing future? Are multiple versions of ourselves existing in parallel universes determined by chance and/or choice? At first, it appears that Cora’s selections result in predicable alternate lives for her son, but Knapp is a cleverer and more talented writer than that. The threads that comprise this family’s life as it splits into three diverge and weave together in unexpected ways.

I found it very moving to see how the supporting characters—an Irish grandmother, a young woman named Lily, various children, a kind veterinarian, a gentle silversmith—appear in varying roles, sometimes integral, sometimes peripheral, sometimes absent altogether. In The Names, we have insight into how the characters are shadowed by the ghostly possibility of different paths; the result of our reading is to wonder with regret or relief about the course of our own lives.