“The more I suffered, the more medical treatments I was convinced I needed, but the more treatments I received, the more I suffered.”

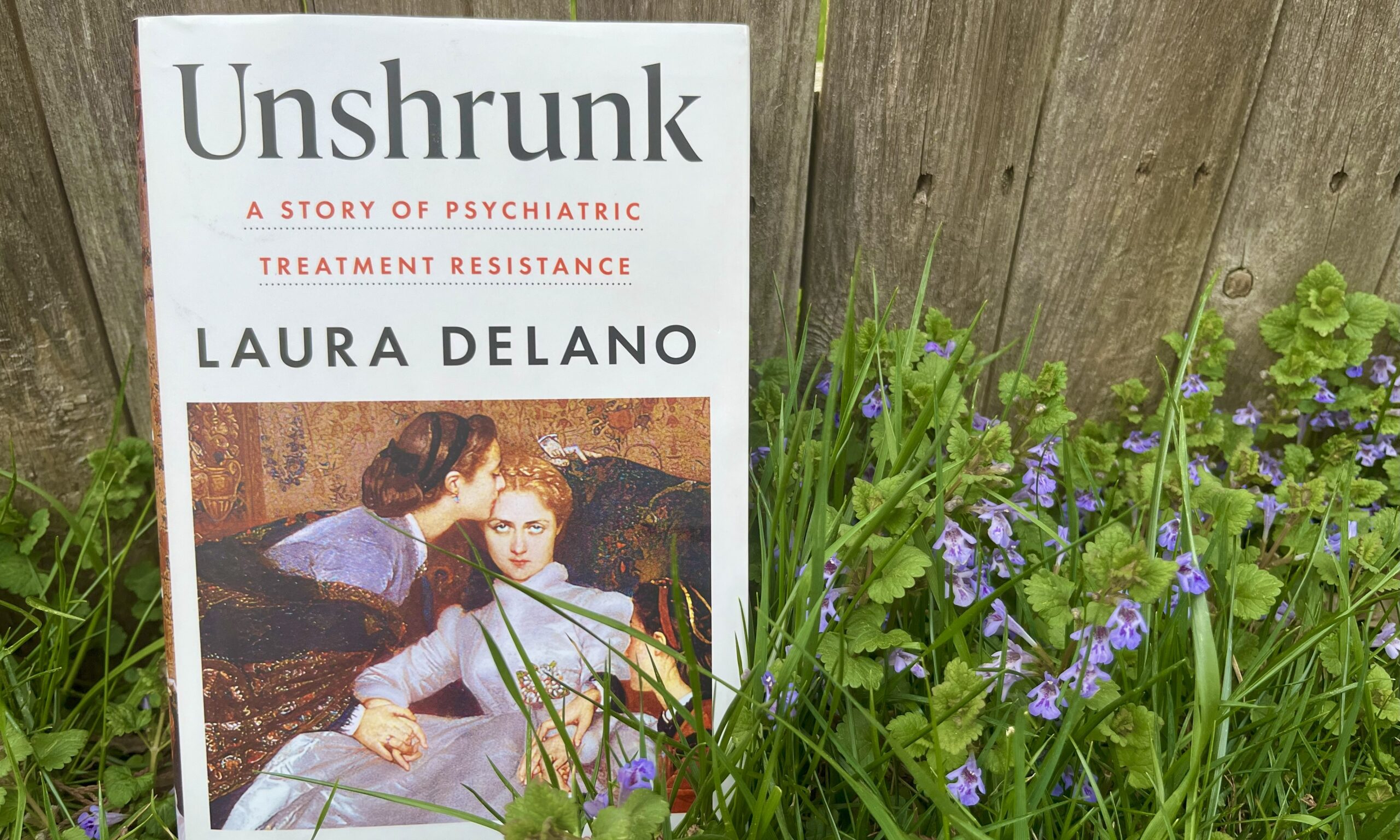

This devastating cycle forms the central paradox of Laura Delano’s gripping memoir, Unshrunk. A descendant of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Delano grew up amid the privilege—and intense societal expectations—of Greenwich, Connecticut. Yet her story makes clear that wealth, family support, and elite access to care do not guarantee protection from profound iatrogenic suffering. In Unshrunk, she offers a raw, unflinching account of her years spent within the mental health industry and her fight to reclaim her life from it.

Between the ages of 14 and 28, Delano’s medical history reads like a scattering of pages torn from the DSM: bipolar disorder (diagnosed at 13), anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance dependence, borderline personality disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder. And then there is her pharmaceutical catalog: five antipsychotics, four mood stabilizers, two antianxiety drugs, Ambien for sleep, Provigil for wakefulness, and six different antidepressants—all prescribed, increased, decreased, abruptly discontinued by doctors intimately familiar with her case. And as her medication regimen expanded, so did her ailments: Hashimoto’s disease, IBS, total loss of sexual function, 70-pound weight fluctuations, chronic pain, and hair loss. In waves she wrestled with suicidal ideation, alcohol and cocaine abuse, and self-harm. She faced four psychiatric hospitalizations and one harrowing suicide attempt. Despite such misery, she somehow managed during those years to graduate “on time” from Deerfield Academy and only five years later from Harvard, where she was a leader on the squash team.

Then, finally, via Alcoholics Anonymous and a chance discovery in a Vermont bookstore, Delano found both the clarity and wherewithal to escape the devastating cycle and heal.

But Unshrunk is not merely a memoir of recovery—it’s also a meticulously researched meditation on a troubling reality. Woven throughout her story is a clear-eyed documentation of our nation’s psychiatric history, including eye-opening statistics from drug trials, critiques of pharmaceutical industry practices, and recovered notes from her own providers.

One minor issue for me, as a reader, is that at times, particularly early in the book, the specific grounds for her diagnoses remain unclear. When Delano first receives a bipolar disorder diagnosis at thirteen, it is not entirely explained which behaviors or symptoms led her first provider to that conclusion. While this ambiguity may mirror her own experience of confusion, it left me curious about what her doctors were seeing—and how that clinical gaze differed from her internal experience.

Delano and her husband now run the Inner Compass Initiative, a nonprofit helping people make more informed choices about diagnoses, drugs, and drug withdrawal. While she is careful to acknowledge that psychiatric drugs provide critical relief for many—and stresses that hers is simply one story—she also poses a provocative challenge: “What will it take for our society to begin questioning the collective assumption that the industries that have made trillions off our worsening pain—among them health, hospital, pharmaceutical, biotech, and tech—are the very ones we should trust to provide us resolution?”

Psychiatric drugs clearly remain essential lifelines for many (including people close to me), but Delano’s story offers a necessary counterbalance to our culture’s knee-jerk medicalization of distress. For anyone navigating the often-murky waters of mental health treatment—patients, loved ones, or even open-minded clinicians—Unshrunk also offers not just critique, but hope: that even after decades of institutionalized suffering, other doors remain open.

At a time when trust in science is eroding, government research budgets are slashed to the bone, and companies profit from the very crises they claim to cure, Unshrunk reads less like a personal reckoning and more like a dispatch from the front lines of a much larger systemic collapse—one that forces us to ask not just how (and why) we suffer, but who we trust to tell us what wellness means…and at what cost.